Poetry Month is officially over, but that’s no reason to abandon our arbitrary and occasional Poetry A-Z series…

L is for Larkin, Philip

Philip Larkin. Sigh. What do we do about Philip Larkin? I want to devote the letter L to Larkin, whose poetry I adore, and yet there’s just so much… awfulness.

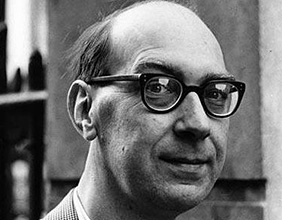

Larkin was never an especially lovable geezer—gloomy, grumpy, and looking, as he described it, “like a balding salmon”—but prior to the publication of his Selected Letters, it was still possible to feel somewhat fond of ol’ Phil. He was just your standard British bachelor-curmudgeon-librarian, keen for a quiet life, fond of rain and queues and animals. Describing his daily routine to the Paris Review in 1982, he wrote:

My life is as simple as I can make it. Work all day, cook, eat, wash up, telephone, hack writing, drink, television in the evenings. I almost never go out. I suppose everyone tries to ignore the passing of time: some people by doing a lot, being in California one year and Japan the next; or there’s my way—making every day and every year exactly the same. Probably neither works.

The man liked to put on his egg-stained cardigan and watch a spot of telly. Nothing wrong with that! And although his most famous poem addresses the horrors of family life, there’s nothing especially strange or sinister in questioning the cycle of generational misery: the popularity of This Be the Verse suggests we all know exactly what he’s talking about.

But with the publication of the Selected Letters in 1992 and Andrew Motion’s biography, Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, the following year, it became clear that Larkin was not just playing the role of the cantankerous old fogey who liked to insist “I loathe abroad.” The letters made plain his rabidly right-wing political views, his misogyny, and his racism: he calls for the “stringing up” of striking miners, for instance, and adds that “the lower-class bastards can no more stop going on strike now than a laboratory rat with an electrode in its brain can stop jumping on a switch to give itself an orgasm.” He also writes of a “terrifying” future in which “we shall all be cowering under our beds as hordes of blacks steal anything they can lay their hands on.”

It was repulsive stuff indeed, and people were quick to take sides. There was a lot of quotes-at-dawn carry on. One critic insisted that Larkin couldn’t possibly be a racist because he once wrote this:

The American Negro is trying to take a step forward that can be compared only to the ending of slavery in the nineteenth century. And despite the dogs, the hosepipes and the burnings, advances have already been made towards giving the Negro his civil rights that would have been inconceivable when Louis Armstrong was a young man. These advances will doubtless continue. They will end only when the Negro is as well-housed, educated and medically cared for as the white man.

And another immediately countered with Larkin at his most vile:

We don’t go to [cricket] Test matches now, too many fucking niggers about.

Poet and critic Tom Paulin described the Letters as a “revolting compilation which imperfectly reveals the sewer under the national monument that Larkin became” and Professor Lisa Jardine referred to Larkin as a “casual, habitual racist and an easy misogynist” and noted that “we don’t tend to teach Larkin much now in my department of English. The Little Englandism he celebrates sits uneasily within our revised curriculum.” Others made excuses. Martin Amis, whose father was great pals with Larkin, suggested the letters merely reveal “a tendency for Larkin to tailor his words according to the recipient.” In his letters to Amis père, Larkin always signed off with some variation of the word bum—C. H. Sisson bum; Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry bum—but it’s rather a leap to suggest that adding an impish bum to the end of a letter is akin to chucking about a few n-words. Yes, we all write things in confidence that we would never say in public, but I’m pretty sure most of us have never written a letter to anyone (not even to Racist Aunt Gladys) in which we refer to “hordes” or “lower-classes.” Some might insist that such sentiments were commonplace back then, to which I would gleefully reply, well, then fuck the lot of them, the mid-century toerags. In any case, this it was different back then stuff is a load of nonsense—the language Larkin used may have read as slightly less shocking at the time, but there’s no denying that his remarks were considered racist by his contemporaries. Many of Larkin’s friends were horrified by the opinions he expressed in private, and Motion says that Larkin was “very unrepentant about his attitudes” and made no special effort to avoid discussing them, even when it was clear they offended the listener.

So, what to make of it all? Do we simply dismiss Larkin as a hateful racist? Or do we ignore the personal (“hey, he wasn’t as bad as Pound!”) and concentrate on the poetry? Motion writes that “the beautiful flower of art grows on a long stem out of often murky material,” and this kind of uneasy admission is perhaps the best we can do. And yet—it doesn’t seem quite enough to say “Okay, yes, Larkin was a bit of a racist; now here are some lovely poems!” Much of Larkin’s appeal comes from his ability to capture the oppressive, dreary pointlessness of life in a post-war England that has lost its faith—that is, ordinary life, lived by ordinary people. As poet X. J. Kennedy states in the New Criterion, Larkin gives us “a poetry from which even people who distrust poetry, most people, can take comfort and delight.” But who are these ordinary people Larkin writes for and about? If he’s racist, misogynistic, and a snob, are his “ordinary people” all middle-class white men? Is he writing for me, too? Do I really want to read a “deeply moving” poem by someone who perhaps suspects that significantly more than half the population is incapable (or undeserving?) of being moved? When I picture Kingsley Amis and Larkin writing sniggery, right-wing, posh-voiced bums to each other, I want to punch them both hard in their ruddy little noses. And yet—

So, what to make of it all? Do we simply dismiss Larkin as a hateful racist? Or do we ignore the personal (“hey, he wasn’t as bad as Pound!”) and concentrate on the poetry? Motion writes that “the beautiful flower of art grows on a long stem out of often murky material,” and this kind of uneasy admission is perhaps the best we can do. And yet—it doesn’t seem quite enough to say “Okay, yes, Larkin was a bit of a racist; now here are some lovely poems!” Much of Larkin’s appeal comes from his ability to capture the oppressive, dreary pointlessness of life in a post-war England that has lost its faith—that is, ordinary life, lived by ordinary people. As poet X. J. Kennedy states in the New Criterion, Larkin gives us “a poetry from which even people who distrust poetry, most people, can take comfort and delight.” But who are these ordinary people Larkin writes for and about? If he’s racist, misogynistic, and a snob, are his “ordinary people” all middle-class white men? Is he writing for me, too? Do I really want to read a “deeply moving” poem by someone who perhaps suspects that significantly more than half the population is incapable (or undeserving?) of being moved? When I picture Kingsley Amis and Larkin writing sniggery, right-wing, posh-voiced bums to each other, I want to punch them both hard in their ruddy little noses. And yet—

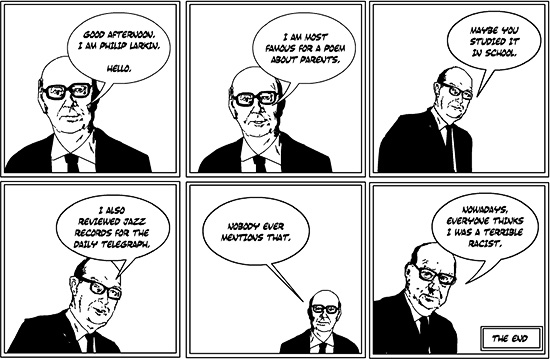

Here I am joining the “Larkin was a bit of a racist; now here are some lovely poems!” chorus, and feeling, yes, very uneasy about it. The best I can do to mitigate the queasiness is present the two Mr. Larkins side by side:

If you skip to the 43:50 mark of Life and Death in Hull (a mildly interesting doco), you can listen to Larkin and his girlfriend singing a little Larkin ditty. If you hear this and still wish to defend Larkin on the grounds that this was done in private (but recorded, do note), or that it’s just meant to be, you know, funny, well, you might not want to invite me to your next dinner party, because I’m not going to laugh at your jokes.

And now here’s the other Larkin, the one I like very much. I’ll leave it to you to try and reconcile the two.

Next, Please

Always too eager for the future, we

Pick up bad habits of expectancy.

Something is always approaching; every day

Till then we say,Watching from a bluff the tiny, clear,

Sparkling armada of promises draw near.

How slow they are! And how much time they waste,

Refusing to make haste!Yet still they leave us holding wretched stalks

Of disappointment, for, though nothing balks

Each big approach, leaning with brasswork prinked,

Each rope distinct,Flagged, and the figurehead with golden tits

Arching our way, it never anchors; it’s

No sooner present than it turns to past.

Right to the lastWe think each one will heave to and unload

All good into our lives, all we are owed

For waiting so devoutly and so long.

But we are wrong:Only one ship is seeking us, a black-

Sailed unfamiliar, towing at her back

A huge and birdless silence. In her wake

No waters breed or break.* * *

The Trees

The trees are coming into leaf

Like something almost being said;

The recent buds relax and spread,

Their greenness is a kind of grief.Is it that they are born again

And we grow old? No, they die too.

Their yearly trick of looking new

Is written down in rings of grain.Yet still the unresting castles thresh

In fullgrown thickness every May.

Last year is dead, they seem to say,

Begin afresh, afresh, afresh.* * *

Aubade

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

—The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused—nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can’t escape,

Yet can’t accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.