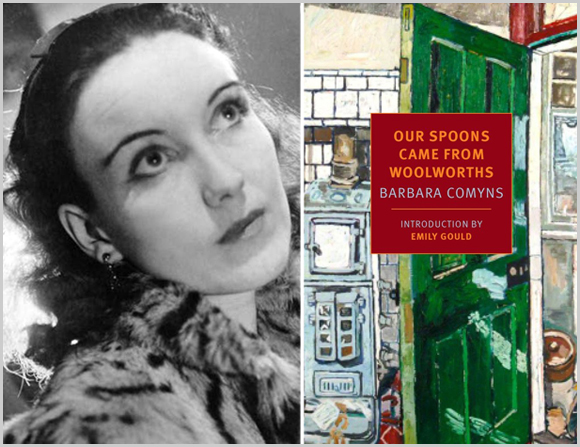

Below, an excerpt from Malvern fave Taisia Kitaiskaia’s wonderful look at the work of English writer Barbara Comyns (you can read the full article here). We stock all of the books Taisia mentions, and we heartily echo her sentiments—Comyns is a fascinating writer and well worth checking out.

Fiction can be frustrating because, while very diverting, it often manages to exclude 99 percent of life on earth. Driven by plot and obsessed with psychology, modern novels tend to behave as if social and human relationships are the only things that matter, as if outer space doesn’t exist, Neanderthals never walked alongside our ancestors, deep-sea fish don’t swim in the dark with their treacherous lights, and our lives aren’t mostly just irrational streams of little pleasures, comforts and discomforts, sleep and dreams. Realist novels especially are disappointingly devoid of creatureliness—that wild, quick, raw stuff we are made of.

But sometimes I come across novelists whose work is alive with wildness. Barbara Comyns is one of these. An underlooked British author of 10 novels—also a painter, mother, evident beauty, breeder of poodles, seller of cars, and doer of other weird jobs to get by—Comyns (1907–1992) has seen a revival of attention after the recent reprinting of her 1985 novel The Juniper Tree. While I hope that this revival earns Comyns’s name a permanent place in the canon, so many women writers are forgotten again even shortly after being remembered. I want to cry, “Read this writer, she deserves it!” But Comyns, dead and gone, doesn’t care if you read her books. It’s you who is missing out.

It’s not as if Comyns’s characters are always pondering Neanderthals (they’re much too stressed), and her novels do sit comfortably enough on the realist shelf. Yet these books are unmistakably feral, thrumming with sinister enchantment and the magical-grotesque possibilities of transformation. When I first encountered Comyns, it was through Who Was Changed and Who Was Dead, which tells of a strange episode in an English village. I finished the short novel in one sitting and then stumbled outside, the book still in my hand. It was almost too alive to either hold or set down, so the thing sweated in my palm like a deranged, flooded, purple Polly Pocket, where a shifty gardener emerges from under the bridge with the body of a dead child, the plastic fairy stands with only one cellophane wing, a power-thirsty grandma hits at crows with her cane, and a tender baker weeps somewhere in the painted distance.

Comyns should have made it into Literary Witches: A Celebration of Magical Women Writers, my collaboration with artist Katy Horan, as she is one of the witchlier writers I’ve read. In addition to her work’s elusive feeling of magic and focus on domesticity—that enduring arena of the witch—it’s Comyns’s creatureliness that most qualifies her. Her books contain an astonishing number of wild things: slugs, insects, eggs, drowning peacocks, paddling pigs, mongooses in kitchens, ducks in drawing-rooms. Creeks and woods and lakes. And, most thrilling of all, her creaturely humans: the barefooted, unsupervised children muddying themselves by the river; the “beastly” (that great Britishism) power-holders, terrorizing and betraying; men and women described as kittens, birds, horses, and even named Mr. Fox; and the shivering animal selves of the female protagonists, hounded but seeking security and reprieve.

Her narratives themselves are wild beings of astonishing velocity and presence, fleeting, unstudied (Comyns was educated haphazardly by governesses in her own deranged Polly Pocket childhood, as described in her 1947 novel Sisters by a River). Her first person narratives are nearly breathless, the sentences like mice scurrying along the edge of the room, single-minded in their pursuit of survival: trying to please, trying not to be noticed, or to be noticed by the right people, trying to scrape by, scared they won’t make it. Comyns’s protagonists, too, are trying to survive, skirting around poverty and vicious, lousy men. These women tell their tales as a mouse might, if you stopped it in its tracks: matter of factly and without self-pity. The narrator of The Vet’s Daughter, Comyns’s most famous book, says of her father: “When I think of him kicking Mother’s front teeth crooked so early in their marriage, it really was a mercy he ignored me, or I might have had a cauliflower ear, or something equally disfiguring.”

Creatures can go many ways. They can be innocent, like the mice skirting around the patriarchy, and they can be beastly like the patriarchy itself. Many of Comyns’s characters are beastly, whether in outright cruelty, as with the father in The Vet’s Daughter, who not only physically and verbally abuses his family, but also sells many of his veterinary subjects to the vivisectionist; or in neglect, as with the autobiographical husband in Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, an arrogant painter who abandons his family. In Who Was Changed: “‘Father makes me hate men,’ thought Emma as she pumped water into the bucket. A slug tumbled out of the pump and she caught it and put it in a dark damp corner of the sink.” The viciousness of the patriarchy has never been so clear as in these books. But what is pleasing about Comyns’s novels is that they’re above easy moralizing, presenting the beasts as they come, knowing that they will sink and die and be reborn again as other creatures.

That leads me to Comyns’s enchantment. There isn’t much explicit magic in her books: The Vet’s Daughter is the only one with unexplained phenomena (and boy, is it wonderful) and The Juniper Tree is intentionally based on a fairy-tale. But all of her books feel like they’re set in the woods even when they take place in towns or cities, and in both the bleakest and most hopeful Comyns moments there is the ripe sense that everything could change. For better or worse, too, many of her novels follow the fairy-tale trope of women saved from poverty and pain by marriage. That the world can be enchanted without also being just or pleasant feels about right. Certainly there are writers who set their books in more thoroughly wild settings, and writers who use fairy tales and folklore more avidly and violently (like that other beastly Brit, Angela Carter). But this is what makes Comyns great: She demonstrates that as we carry out ordinary lives in cities, as we run around and try to make ends meet and find partners and friendly souls, we are little animals there, too… (continue reading).

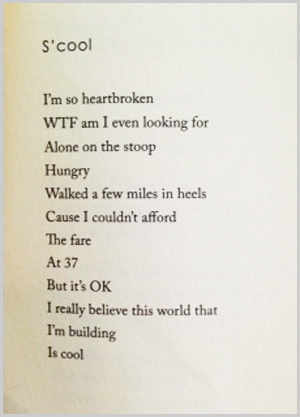

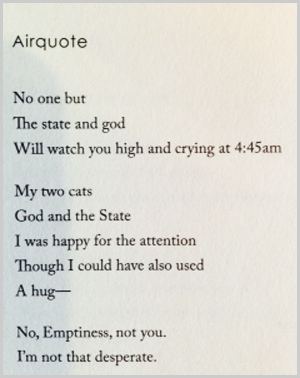

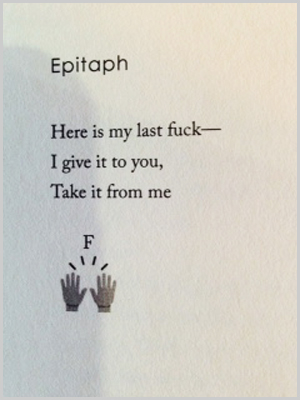

Walking home from the first meeting of Line/Break (

Walking home from the first meeting of Line/Break (

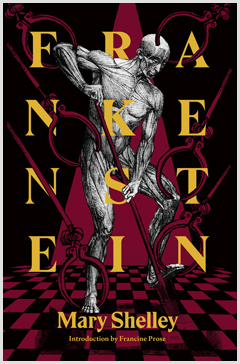

Out of the canonical monsters, could the monster in Frankenstein be the most relatable? Who doesn’t sometimes feel like an amalgam of rotting appendages that have to be animated back to life with electricity?

Out of the canonical monsters, could the monster in Frankenstein be the most relatable? Who doesn’t sometimes feel like an amalgam of rotting appendages that have to be animated back to life with electricity?