Julie recommends Making It by Norman Podhoretz:

According to Norman Podhoretz everyone worships Success—that buxom Goddess who nurses her four hungry babes: Money, Power, Fame and Social Position. And if we, mere mortals, can’t admit to bowing to all four minor deities, he’s convinced that each of us curtsies to at least one. “Success” as he quotes William James “is our national disease.” It is a disease stemming from a culture that leaves its citizens in limbo “teach[ing] us to shape our lives in accordance with the hunger for worldly things” even while it “spitefully contrives to make us ashamed of the presence of those hungers.”

According to Norman Podhoretz everyone worships Success—that buxom Goddess who nurses her four hungry babes: Money, Power, Fame and Social Position. And if we, mere mortals, can’t admit to bowing to all four minor deities, he’s convinced that each of us curtsies to at least one. “Success” as he quotes William James “is our national disease.” It is a disease stemming from a culture that leaves its citizens in limbo “teach[ing] us to shape our lives in accordance with the hunger for worldly things” even while it “spitefully contrives to make us ashamed of the presence of those hungers.”

Like a moth to a flame, it was the title of Making It that caught my attention; here was a literary looking NYRB memoir that I could sneakily read as a self-help book or how-to guide. Podhoretz covers territory that holds a deep personal interest for me—his is a classic bootstrap story: poor kid gains admission into an ivy league school, Columbia, then heads off to Cambridge, returns to New York to land a job at Commentary, a prestigious magazine in Manhattan, gets welcomed into the fold of a tight-knit circle of literary hotshots, and ascends to further glory (with, of course, a few bumps along the way). If that storyline wasn’t enough of a sell, the opening introduction alone made me willingly toss more of my hard-earned bookseller money back into books. He writes:

Let me introduce myself. I am a man who at the precocious age of thirty-five experienced an astonishing revelation: it is better to be a success than a failure.

I, too, at the age of thirty-seven had recently struck upon this same idea! On my walk to work, I interrogated the very notion of “success” as it relates to the capitalist patriarchy for about the length of time it takes to sneeze (it’s allergy season here) and watched a glossy new Porsche drive by. Did I want to live like a Kardashian? Ew, gross. Did I want a bunch of hotels with my name on them? Hell no. But with some sixty-second soul searching, I concluded that I did indeed want to pal up with three out of four demigods, money, power, and fame. It would be nice, right?

Podhoretz is quick to clarify that success is not exclusively about money, “just as often it might mean prestige or popularity.” A job as a doctor, or, in today’s terms, someone with 500k Instagram followers. Growing up in Brooklyn to Jewish parents of modest means he understood that “the main thing was to be esteemed.”

Even as a young boy, Podhoretz was keenly aware that people belonged to different classes and that meant something: “I and everyone I knew were stamped as inferior: we were lower class.” The words “Slum child, filthy little slum child,” were flung at him by his teacher, Mrs. K, a woman determined to turn young Podhoretz into her pet project so that he might, with some polishing, win a scholarship to Harvard. “[S]he treated me like a callous, ungrateful adolescent lover on whom she had humiliatingly bestowed her favors. She flirted with me and flattered me, scolded me and insulted me,” he writes. The scenes that he recounts of Mrs. K teaching him to dress right, eat right, talk right are brutal, but also captivating to read. “Good manners to Mrs. K. meant only one thing: conformity to a highly stylized set of surface habits…” He did go on to succeed on Mrs. K’s terms and got into Harvard with a scholarship but it still wasn’t enough to cover all expenses so he attended Columbia.

For all his early success Podhoretz likens jumping the class barrier to moving to a foreign country. He writes:

That country is sometimes called the upper middle class; and indeed I am a member of that class, less by virtue of my income than by virtue of the way my speech is accented, the way I dress, the way I furnish my home, the way I entertain and am entertained, the way I educate my children—the way, quite simply, I look and live.

He describes the process of self-fashioning—from slum child to acclaimed critic and editor—with cool detachment, but just as swiftly comes a heartwrenching admission:

It appalls me to think what an immense transformation I had to work on myself in order to become what I have become: if I had known what I was doing I would surely not have been able to do it. . . No wonder the choice had to be blind; there was a kind of treason in it: treason toward my family, treason toward my friends. In choosing the road I chose, I was pronouncing a judgment upon them, and the fact that they themselves concurred in the judgment makes the whole thing sadder but no less cruel.

I don’t think I’ve ever encountered the “disloyal” aspects of upward mobility articulated so poignantly before. As a first generation college student, who like Podhoretz also attended Columbia, I certainly related. (When I broke the news that I’d gotten into Columbia, I had to clarify that I wasn’t talking about the country. Indeed, both places were equally mysterious to many in my family.)

After Podhoretz rises far above the menial jobs that could have been his lot in life, he wonders if he could ever untie himself from ambition’s constant tug and disappear back into a simpler life. He toys with the idea of becoming a janitor in order to give up his desires for “things,” and his unsettling “need for power.”

I will admit it was a bit strange to develop such a fondness for a man who helped put the neo in neoconservative—perhaps hinted at best in a 2010 editorial Podhoretz wrote in the Wall Street Journal titled, “In Defense of Sarah Palin.” And there are moments in Making It that are cringeworthy, such as Podhoretz’s fixation with personal slights. When James Baldwin supposedly stiffed him a promised essay that went on to be published, not in Commentary, but in The New Yorker “[he] saw what a precious item had been stolen from [him],” that essay being “The Fire Next Time.”

The names associated with “making it” today aren’t writers, critics, or intellectuals, but billionaires with their own space vessels and walled off portions of islands. I confess I had to look up Commentary to see if it was still even afloat. It was a bit surreal to measure this book against the news today. Maybe it’s just me but success, now more than ever, seems to involve steamrolling over others, or using deceptive means to, say, gain the highest office in government. Podhoretz’s work is filled with hard-won insights into the human psyche: our fascination with having it all, our fear of having it all and losing it—this memoir is truly outstanding. I’m still haunted by what Lionel Trilling said to Podhoretz when he was a young writer; he said, “Everyone wants power. The only question is what kind.”

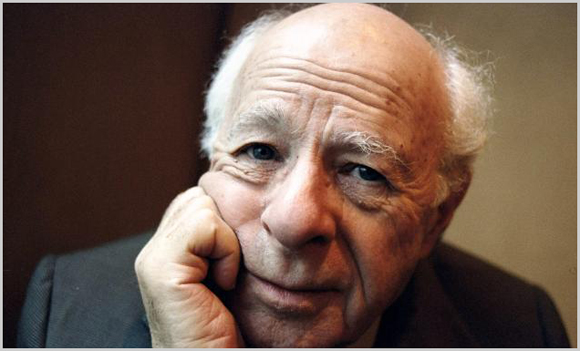

Photo credit: JON NASO/NY DAILY NEWS ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES