Celia recommends Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl by Andrea Lawlor:

How should I begin talking about this book? I ask this question because sometimes it can be difficult to talk about novels that embrace happiness and laughter. If I mention that this book is hilarious, one wonders, is it going to sound, like, unserious? If I mention that I repeatedly laughed aloud and made my coworkers stare at me while reading this book in the store, will readers perhaps assume that I am just more amused than the average person by jokes about ‘90s queer theory and punk rock? Maybe, dear reader! But sometimes you find a book that moves so lightly through its changes that, although its subject may be heartbreak, failure, the AIDS crisis, and its hero’s inability to find a place to belong, it nevertheless buoys you up, makes you laugh at work, and assures you that this, too, shall pass.

How should I begin talking about this book? I ask this question because sometimes it can be difficult to talk about novels that embrace happiness and laughter. If I mention that this book is hilarious, one wonders, is it going to sound, like, unserious? If I mention that I repeatedly laughed aloud and made my coworkers stare at me while reading this book in the store, will readers perhaps assume that I am just more amused than the average person by jokes about ‘90s queer theory and punk rock? Maybe, dear reader! But sometimes you find a book that moves so lightly through its changes that, although its subject may be heartbreak, failure, the AIDS crisis, and its hero’s inability to find a place to belong, it nevertheless buoys you up, makes you laugh at work, and assures you that this, too, shall pass.

Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl is one of these books. The novel’s hero, Paul Polydoris, has an unusual talent: he can change his body at will, beefing up his arms to look like a muscle man, slimming down, making himself taller or shorter, growing a beard on command—and he can turn himself into a woman. He does so in the first scene of the novel, in which he first carefully coordinates his outfit to go to a lesbian punk show, and then, “stares at his penis until it shrinks [and] tucks itself into the tight little crawlspace of his former balls.” (NB: This is perhaps not the book for you if you don’t want to read descriptions of sex or genitalia. There are quite a few of them, explicit and haplessly funny. I’ll also say, at this point, that I’m using the pronoun “he” for Paul advisedly, for while he spends a large portion of the novel living as a woman, he always uses male pronouns in narration. Another, similarly fluid character effortlessly avoids using any pronoun at all.)

From the opening moment when Paul turns himself into a woman (his lesbian best friend, meeting him at the show, thinks he’s just doing an exceptionally good drag act), the novel circles around its central questions, teasing the reader without quite revealing any definite solutions. How did Paul become the way he is? What fuels his ability to change? Will he have to pick one form, or will he be able to stay varied and changeable, bisexual, bi-gendered, and fluid? Who will he hook up with next? Does the androgynous youth he keeps glimpsing in various gay hot spots know the secret of their shared shapeshifting? What’s up with the impossibly tough leftist lesbian he meets at Michfest, who can maybe talk to animals? Will he be able to juggle his half-dozen minimum wage jobs in order to make rent this month? What if he wants to make rent and buy the cool jacket he found at the vintage store?

The novel tackles these questions irreverently, letting Paul wander around, flirting his way to free coffee, skipping out on his college classes, baffling his friends and colleagues. He goes to an employee party for a sports bar, and, bored by the frat boy atmosphere, leaves and comes back as his own sister. He lets his best friend in on his secret and convinces her to go to Michfest with him. He does a knock-down performance of machismo at a leather bar. He moves to Provincetown to live as a woman with his new girlfriend. He has an enormous amount of sex—in bathrooms at parties, in bars, public parks, alleys, woods, and the comfort of his own bed. He is endlessly hungry to be seen, admired, loved. He is continually buying new records and clothes instead of paying his utility bill, in a kind of exhausted surrender to his endless need for new experiences. His life is a kind of balancing act. There are threats under the wire: he may lose his apartment. He may drop out of school. He may face homophobic violence, or rejection by the next person who sees him change his body.

Also, the book is set in the early ‘90s, and Paul has just fled from New York, where the AIDS crisis is still devastating the queer community. When he runs—to Iowa, Chicago, Provincetown, San Francisco, to the next hook-up, boyfriend, or girlfriend—he is running, in part, from death. Somehow, he always seems to escape the worst thing.

When tragedy does strike, it feels (as often enough in life) as if this is the end, the disaster, the worst thing. Will he ever get out of bed again? Ever wake up and not want to start the day by drinking? Ever find another person he wants to kiss? Yes, dear reader, he does—eventually. This is a book in which the love of life, though it doesn’t bring about any straightforward fairy tale endings, is strong enough to overcome sorrow. I’ll leave you with the novel’s last line (one can do this, with this book, without particularly spoiling anything): “He saw the city, as good-smelling and various as himself.”

Ask Baba Yaga: Otherworldly Advice for Everyday Troubles

Ask Baba Yaga: Otherworldly Advice for Everyday Troubles

Eve Babitz, see all (

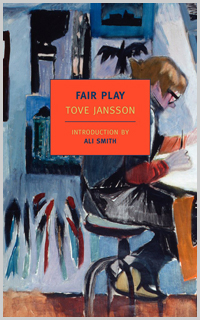

Eve Babitz, see all ( Fair Play

Fair Play