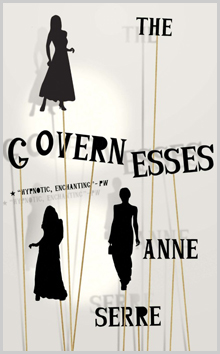

Celia recommends The Governesses by Anne Serre:

Sometimes an ordinary piece of information startles you. For instance: reading about Anne Serre in preparation for writing this review, I discovered the publication date of the original French version of her novel The Governesses: 1992. I regret to inform you that I stopped reading right there, closed the tab of French Wikipedia on my browser, and will be offering you absolutely no anecdotes from Anne Serre’s life.

Sometimes an ordinary piece of information startles you. For instance: reading about Anne Serre in preparation for writing this review, I discovered the publication date of the original French version of her novel The Governesses: 1992. I regret to inform you that I stopped reading right there, closed the tab of French Wikipedia on my browser, and will be offering you absolutely no anecdotes from Anne Serre’s life.

It’s not that the date itself is implausible, but that it had the strange effect of providing an anchor point for a book that feels as if it has sprung fully formed from the air. The Governesses could as easily be a Victorian experiment by the likes of Christina Rossetti, or a novel written just this year, and still on the cutting edge. It’s difficult to picture Serre writing it, in the same way that it’s difficult to picture the craftsmanship of a Fabergé egg, that perfect, jewel-encrusted world unto itself. And yet this is a novel that asks its reader to think deeply about the act of creation, and about the nature of the created world.

The premise of the novel is familiar: a family hires a governess. Or rather, three governesses. Two look after the troop of small boys (only boys) who roam the gardens of the manor house, climbing trees and catching frogs. The other cares for the old man across the way. But the governesses do very little teaching or child-rearing, and there are too many little boys for them to be the children of Madame and Monsieur Austeur, who own the house, and the old man spends most of his time glued to his window, watching the governesses wander through the gardens of the house. They, aware of his gaze, don’t seem to mind. Sometimes they strip nude and make up tableaus, to entertain themselves and him. Sometimes they encounter a strange man in the gardens, and then they chase him down and eat him. Or make love to him. It’s approximately the same thing, really.

The whole slim novel teeters between the extremes of two powers: on the one hand, there is the wildness of the governesses, their changeable passions, the transporting force of their desire. Planning a party, “they had clanged so many cymbals and banged so many drums that every man and woman for miles around, and even a few curious dogs, had come trotting over to gaze hungrily at the scene through the garden gates.” And, at the other pole, the bestilled equilibrium of the Victorian novel, the setting in which nothing can ever truly change, and every new event is assimilated back into the status quo. So, when the governesses come to the manor house: “all the trees they had ever known—the ones in the school playground, for example, and the ones outside grandma’s house and along the road to the beach—came rushing into Monsieur and Madame Austeur’s garden, lining up side by side with the elms and the oaks, and then disappearing inside them. The same thing happened with houses, barns, chateaux, and whole towns. They all came storming in through the wide-open gates the morning of the governesses’ arrival.”

The manor house eats the governesses’ past, and they become—what? Part nymph, part maenad, part prim young ladies. There’s a tyranny beneath the beauty of Anne Serre’s fiction. How many remembered trees does it require to make one of those imaginary oaks or elms? What is this thing, the novel, that takes no account of the outer world, bowing only to its own internal structures? The governesses, for all of their wildness, are trapped within a cyclical, enclosed world, in which all of their reckless libertinism cannot upset the status quo. Take them outside of it, and they are nothing.

And so within the novel’s wild flights of fancy, there is a core of melancholy.