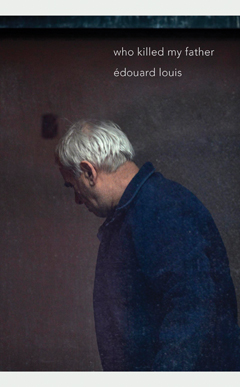

Julie recommends Who Killed My Father by Édouard Louis:

What does it mean for a book to provoke, to register on a visceral level like a disturbing movie scene that you can’t un-see? As I read Who Killed My Father by Édouard Louis I thought a great deal about provocation, its outcomes anger, sadness, frustration, a sense of reliving emotions to a boiling point. Louis’s vivid portrait of how the class system in France chipped away at his father’s body, mind, and spirit reminded me of the state of things for so many Americans who make $7.25 an hour in 29 states including Washington DC in the year 2019. I thought of members of my own family, told by dentists that there’s nothing to be done to save their teeth. I thought about foreclosures, health insurance, food stamps and the ways in which the poor are required to submit documented proof of near destitution over and over and over again. I thought about shame.

What does it mean for a book to provoke, to register on a visceral level like a disturbing movie scene that you can’t un-see? As I read Who Killed My Father by Édouard Louis I thought a great deal about provocation, its outcomes anger, sadness, frustration, a sense of reliving emotions to a boiling point. Louis’s vivid portrait of how the class system in France chipped away at his father’s body, mind, and spirit reminded me of the state of things for so many Americans who make $7.25 an hour in 29 states including Washington DC in the year 2019. I thought of members of my own family, told by dentists that there’s nothing to be done to save their teeth. I thought about foreclosures, health insurance, food stamps and the ways in which the poor are required to submit documented proof of near destitution over and over and over again. I thought about shame.

We know what poverty looks like, but not everyone is familiar with what it does, its function on the individual as well as the family unit. Louis asks us to imagine a stage with two figures, a father and a son. The son is an interpreter for the father. The father has gone silent. The son is in charge of conveying the father’s condition. The son is gay, and this complicates their relationship further, makes it even more difficult to relay the story. “The son speaks, and only the son, and this does violence to them both.” No matter how well the son speaks for the father, tells his story, their story, estrangement is still the unfortunate result.

To see his father from an objective stance, in order to take in all the changes he sees, Louis writes to him.

He writes, “In your face I read the signs of the years I’d been away.” The son begins to make a mental note of all the changes in his father’s mobility. “When you got up to go to the bathroom, just walking the thirty feet there and back left you winded. I saw myself, you had to sit and catch your breath.” He catalogs the changes to his father’s physique. “Your body has grown too heavy for itself. Your belly stretches towards the floor. It is overstretched so badly that it has ruptured your abdominal lining.”

A letter of this sort is meant to be burned. Who Killed My Father is a book that navigates what can’t be said, it addresses liminal spaces; it drifts between present and past tense; it glides between first and second person; it eulogizes a man who is still alive. At under 85 pages the book captures so completely the atrocities committed within families when poverty pits them against one another. For Louis’s father, reading is considered weak, education effeminate. It’s only the brute strength of defiance that’s respected.

Louis writes:

For you, constructing a masculine body meant resisting the school system … constructing your masculinity meant depriving yourself of any other life, any other future, any other prospect that school might have opened up. Your manhood condemned you to poverty, to lack of money. Hatred of homosexuality = poverty.

Sound familiar? This sort of masculinity cannot be reasoned with. Passages such as these are brilliant for the truth they contain. At times though, Louis’s analysis is confounding. He quotes the American scholar Ruth Gilmore, who said, “racism is the exposure of certain populations to premature death.” He seems to apply this definition to the plight of white working class French citizens, like his barely fifty-year-old father, forgotten by the government. He adds, “The same definition holds with regard to male privilege, to hatred of homosexuality or trans people, to domination by class—to social and political oppression of all kinds.” I just don’t suspect that Gilmore intended her definition to be this flexible. The non-specific “certain populations” I understood to mean people of color, people marginalized because they are not white. In this country, it would certainly be frightening to say that impoverished working class whites from Trump-infused red states are victims of racism (although some seem to think they are).

Called a “young superstar,” a literary wunderkind, Édouard Louis (age 26) rose to artistic fame quickly. I will admit, I became completely enamored with him and his writing, and after finishing Who Killed My Father, rushed out to get The End of Eddy and History of Violence. Both books navigate the subjects of rape, abuse, homophobia, xenophobia, racism and class, and the work does so in a way that feels utterly urgent. I can think of few young writers who manage to situate themselves so squarely within their time, as Louis does. He does so bravely, taking risks where others would be afraid. He knows, for instance, that it’s somewhat controversial to criticize Emmanuel Macron, when the Marine Le Pens of the world are salivating for more power.

I thought of The Yellow Vest Movement; Brexit; Notre Dame in flames; The Paris Climate Pact; and the surreal experience I had just weeks ago in my own homeland of being in Newark International Airport and seeing red “Make America Great Again” t-shirts and hats for sale in an over-priced tchotchke store. With a book like Who Killed My Father, the alignment with current events seems to hover at the corners of the page.