Stephanie recommends Before Lyricism by Eleni Vakalo:

Stephanie recommends Before Lyricism by Eleni Vakalo:

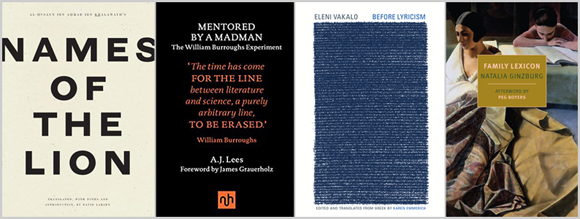

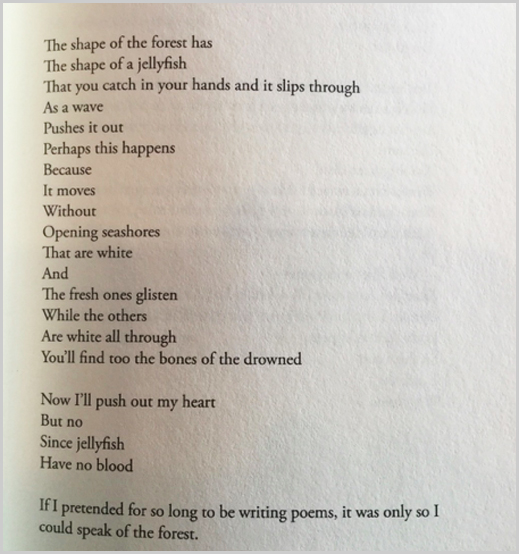

Before Lyricism by Eleni Vakalo—via translator Karen Emmerich and publisher Ugly Duckling Presse—is perhaps my favorite poetry book published in English last year, despite the book’s explicit discussion of poetry itself, which I confess is something I tend to loathe (and of course also something I hypocritically do myself as a poet). I mention this (and mention it early) only to encourage readers who might be quickly turned off by Poetry Talk in Poems to stick with Before Lyricism because the book is a beautiful and strange trek through entrancing turns of phrase and image.

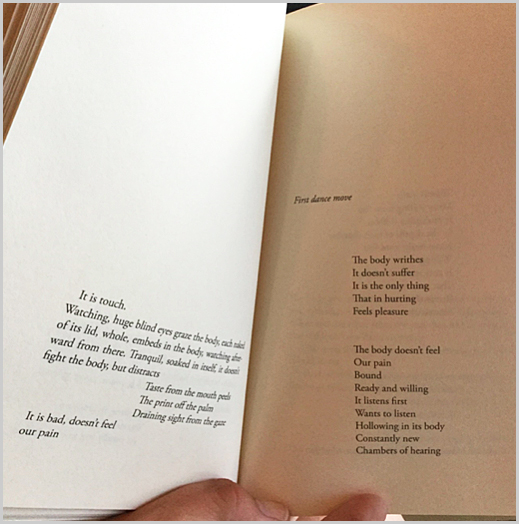

Turns of phrase as in lyrical expressions, yes. Also turns of phrase as in a series of words folding in on itself before expanding into additional meanings. And also turns of phrase as in a dance, the phrase a unit composed of bodily gestures, the dancer moving, turning. The poems in this book first and foremost are “about” no first and foremost, the text being concerned with the sort of ambiguity generated by turns of phrase.

Turns of phrase as in lyrical expressions, yes. Also turns of phrase as in a series of words folding in on itself before expanding into additional meanings. And also turns of phrase as in a dance, the phrase a unit composed of bodily gestures, the dancer moving, turning. The poems in this book first and foremost are “about” no first and foremost, the text being concerned with the sort of ambiguity generated by turns of phrase.

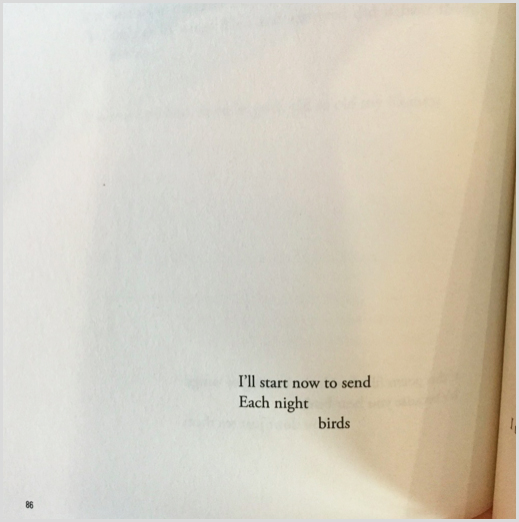

While Vakalo is fond of introductory textual notes like “Poetic Fiction (in the style of an expressive ballet)” and “From the diary of the poem,” Before Lyricism embraces so many readings of the text, often line by line, that a reader uninterested in the Poetry Talk can quite easily just ignore it. The pleasure I first took (and ultimately return to) with this book is the pleasure I draw from its images and sounds. I see the word “poem” in the text and kind of skip it; I’d rather think of a bird as a bird than as a poem, you know? So if you feel similarly, it’s important to me that you know this gorgeous book is still for you.

The poems in Before Lyricism—the first Vakalo book in English translation, courtesy a decade of dedication from Emmerich, recently awarded the Best Translated Book Award of 2018 for the work—are interested in composition (of art, of a body, of meaning, of image, of ourselves) as expressed through language/image/movement. Vakalo, a Greek art critic and art historian who lived from 1921 to 2001, writes in wild lines—wild in the sense that they seem to express freedom of movement, with no poem in the book adhering to a single visual form throughout its pages.

The poems in Before Lyricism—the first Vakalo book in English translation, courtesy a decade of dedication from Emmerich, recently awarded the Best Translated Book Award of 2018 for the work—are interested in composition (of art, of a body, of meaning, of image, of ourselves) as expressed through language/image/movement. Vakalo, a Greek art critic and art historian who lived from 1921 to 2001, writes in wild lines—wild in the sense that they seem to express freedom of movement, with no poem in the book adhering to a single visual form throughout its pages.

Or as Emmerich puts it in her translator’s note: “the six book-poems I present here are what Andreas Karandonis described as ‘experiment-objects,’ which treat the book as a tactile object with features to be explored as elements of poetic composition. Her pages and spreads often display sprawling yet deliberate assortments of prose, free verse, and even rhymed and metered lines, a mixture of styles and registers that can be both heard and seen.”

(Or as Vakalo herself writes in one of the poems: “hugging the wall touching the objects one by one adjusting their positions I come to know them.”)

Vakalo saw the six book-length poems collected here as parts of a larger whole. In addition to an interest in composition, each poem (“The Forest,” “Plant Upbringing,” “Diary of Age,” “Description of the Body,” “The Meaning of the Blind,” and “Our Way of Being in Danger”) interrogates pleasure and fear, which the speaker(s) might say are what exists before lyricism, before sense, before the sensory, before song.

And of course after, too.

“How we exist is governed by how we take pleasure,” Vakalo writes. Take pleasure as in how do we receive it? Take pleasure as in from what/where do we remove it? To where do we carry it? How do our bodies transport it? What changes to it or the landscape it came from or the body that receives it then occur? Anyone with an interest in not answering those questions will take pleasure in Before Lyricism, as I do each time I reread it.