Ahoy there, Malvernians! I trust your Labor Day was not the least bit laborious. I’d hoped to spend the weekend reclining on a chaise lounge with a good book, a plate of tropical fruit, and a basket of frolicking kittens, but alas the longed for book/mango/cat trifecta was not to be. Instead, I was dragged off to the wilds of Western Massachusetts to experience an alarming cabin/woods/salamanders combo in the Berkshire Hills. (My fear of the outdoors was slightly lessened by the place’s silly name: berk is affectionate colonial slang for an idiot, and thus I was able to spend the entire weekend imagining myself in a mountainous land of fools.) The Berkshires are popular for terrible activities like hiking to waterfalls and striking unsuspecting deer with your car. Fortunately for us indoorsy types, the region’s most impressive hill offers up a little literary distraction…

I’m talking about Mount Greylock, where Henry David Thoreau got his groove back. At 3,491 feet, Greylock is the highest point in Massachusetts, and on a clear day you can see five states from the top. It’s also part of the legendary Appalachian Trail—and a bloody tough part, it seems. In Bill Bryson’s A Walk in the Woods, his account of hiking the trail, Bryson describes his Greylock climb as “steep, hot, and seemingly endless.” And, to add to the thrill of the infinite uphill slog, there are also black bears, bobcats, and coyotes cavorting among the boreal bushes.

Fortunately, you don’t have to hike up there; you can drive the seven miles to the summit on a winding, mist-shrouded road. And once you’re at the top, you can celebrate your good sense with a beer from the bar at Bascom Lodge, a rustic ’30s hotel that seems to be run by a bunch of frazzled but friendly New Zealanders.

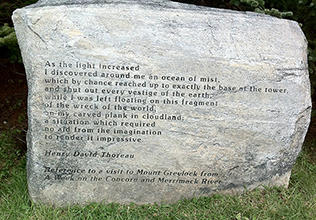

As for Thoreau, he left his Toyota at home and hiked to the summit in July 1844. He spent the night up there by himself and penned a few lines:

As for Thoreau, he left his Toyota at home and hiked to the summit in July 1844. He spent the night up there by himself and penned a few lines:

As the light increased

I discovered around me an ocean of mist,

which by chance reached up to exactly the base of the tower,

and shut out every vestige of the earth,

while I was left floating on this fragment

of the wreck of the world,

on my carved plank in cloudland;

a situation which required,

no aid from the imagination

to render it impressive.

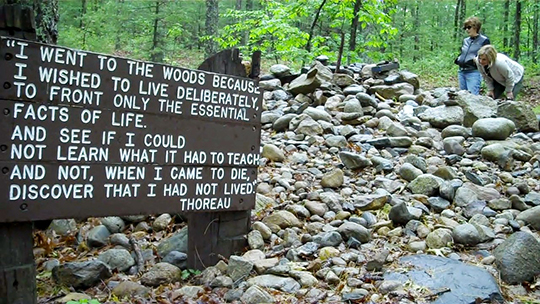

According to scholars, this night alone on the mountain transformed Thoreau. You see, at the time of his Greylock adventure, Thoreau was still in mourning for his brother John, who’d contracted tetanus from a shaving cut (!) and had died in Thoreau’s arms in 1842. The two brothers had been very close and John had always accompanied Henry on his woodsy wanderings. Following his brother’s death, Thoreau suffered a crisis of confidence and began to question his abilities as an outdoorsman. However, climbing Greylock alone proved to Thoreau that he was capable of making pointless and difficult excursions all by himself, and this gave him the courage he needed to begin his great Walden experiment the following year.

According to scholars, this night alone on the mountain transformed Thoreau. You see, at the time of his Greylock adventure, Thoreau was still in mourning for his brother John, who’d contracted tetanus from a shaving cut (!) and had died in Thoreau’s arms in 1842. The two brothers had been very close and John had always accompanied Henry on his woodsy wanderings. Following his brother’s death, Thoreau suffered a crisis of confidence and began to question his abilities as an outdoorsman. However, climbing Greylock alone proved to Thoreau that he was capable of making pointless and difficult excursions all by himself, and this gave him the courage he needed to begin his great Walden experiment the following year.

And Thoreau wasn’t the only nineteenth-century literary bloke to be inspired by the mighty monadnock. Herman Melville had a lovely view of the Berkshires from his home in nearby Pittsfield—he even built a special deck for Greylock-gazing—and the snow-covered outline of the mountain reminded him of a great white whale emerging from the sea. You know how the rest of the story goes. Nathaniel Hawthorne also climbed to the top on a number of occasions and was moved to write the story “Ethan Brand” after he stumbled upon a burning lime kiln on a midnight Greylock stroll. None of that makes any sense to me—burning lime kiln? midnight stroll?—but it sounds terribly dramatic.

And speaking of mountaintop fun, I recommend the Greylock drinking game, in which a sip of beer must be taken every time a wild-eyed man stumbles in off the trail sporting a colossal beard and sixty-seven gaudy bruises. You will all be sloshed very quickly.

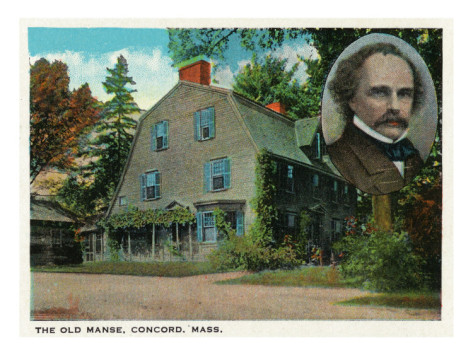

In 1842, newlyweds Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) and his wife Sophia rented the Manse for $100 a year. Since brushed chrome toasters and Le Creuset cookware had not yet been invented, their pal Thoreau planted a vegetable garden for them as a wedding gift. Nathaniel and Sophia were batty about each other, and on a tour of the Manse you’ll see the poems they wrote for each other etched into the Manse’s windowpanes with Sophia’s diamond ring. You’ll also meet Longfellow, Hawthorne’s spooky stuffed owl, which he would hide around the house to frighten his wife. Alas, after three happy years at the Manse (during which Hawthorne wrote a tribute to the house called Mosses from an Old Manse), the Hawthorne’s were evicted for not paying rent.

In 1842, newlyweds Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) and his wife Sophia rented the Manse for $100 a year. Since brushed chrome toasters and Le Creuset cookware had not yet been invented, their pal Thoreau planted a vegetable garden for them as a wedding gift. Nathaniel and Sophia were batty about each other, and on a tour of the Manse you’ll see the poems they wrote for each other etched into the Manse’s windowpanes with Sophia’s diamond ring. You’ll also meet Longfellow, Hawthorne’s spooky stuffed owl, which he would hide around the house to frighten his wife. Alas, after three happy years at the Manse (during which Hawthorne wrote a tribute to the house called Mosses from an Old Manse), the Hawthorne’s were evicted for not paying rent.