Poetry Month is officially over, but that’s no reason to abandon our arbitrary and occasional Poetry A-Z series…

M is for Manhire, Bill

Ask a New Zealander to name a contemporary Kiwi poet—a lively game for dinner parties, if you can get hold of a New Zealander—and they’re almost certain to say Bill Manhire. (Ask your antipodean to quote a few lines, and they’ll wrinkle their sunburnt nose and say, “Oh, I don’t know any poems off by heart…” and then they’ll look all shy and take a massive swig of wine.)

Bill Manhire was born in Invercargill in 1946. For those of you who insist on picturing bucolic, hobbity loveliness whenever someone says “New Zealand,” please note that Invercargill is a gray, gloomy town at the bottom of the world. It looks like this (and if ever you need proof that human beings are inherently optimistic, consider the person who planted the weird shrub-like thing and thought, “Oh, this’ll cheer the place up a bit”):

The son of a publican, Manhire grew up in small hotels in southern New Zealand, an experience he writes about movingly in his short memoir, Under The Influence (Four Winds Press, 2003):

At the St. Kilda Hotel there was a pensioner called Henry who used to come into the bar in the mornings. He lived in a shed in someone’s small backyard, and a rich smell always kept him company. The bar staff liked Henry, and wanted to let him have a drink, but they had to keep the comfort of other customers in mind. So before he was served, Henry would wait patiently until he had been sprayed with air freshener. He would raise his arms like a child hoping to be lifted. Sometimes he smelt of lemons, sometimes of roses.

Manhire was educated at the University of Otago and University College, London, where he studied Old Icelandic sagas (he can still pronounce “Eyjafjallajökull”). His first book of poems, The Elaboration (featuring drawings by acclaimed New Zealand artist Ralph Hotere), came out in 1972. He has since published fifteen poetry collections, and has won the New Zealand Book Award for Poetry five times. He became the inaugural New Zealand Poet Laureate in 1997, and in 2004 he was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (an order of chivalry given by the Queen to top-notch citizens of her commonwealth). His poetry collections get reviewed by fancy papers and his poems get published in fancy places (Google tells me this 2009 poem contains the New Yorker’s sole reference to “Asian bukkake”).

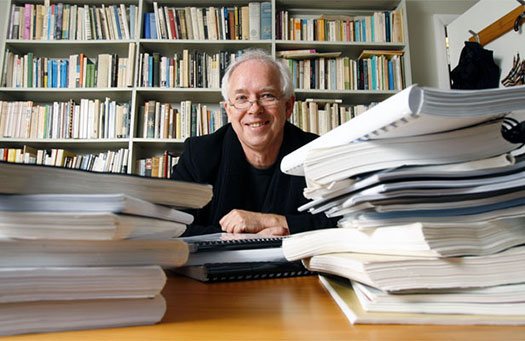

Manhire has also played a significant role in fostering New Zealand literature. He founded the country’s first creative writing course at Victoria University of Wellington in 1975, and he recently retired after a long career as the director of the International Institute of Modern Letters (disclosure: I was a student in his MA class in 2003, and will be forever grateful to him for gently dissuading me from my obsession with writing about women in comas). According to a Dominion Post article, he wants to spend his retirement being a “proper writer” again, a prospect that could be “quite scary.”

In a 2003 interview for World Literature Today, Manhire remarked that “most people are mildly puzzled by my work.” And it’s true, his poetry is often referred to as elliptical, allusive, maddeningly enigmatic (much like Manhire himself, it has been suggested; regarding his tendency to be “secret and reserved and private,” he told World Literature Today that “I’m not sure that’s a good thing in me as a person, but I kind of like it in the poems”). But his poetry can also be playful, whimsical, a bit silly. (Self-important writers, Manhire told The Listener, “are the worst sort of human being.”) He likes to repurpose the banal idioms of popular culture, rendering the ordinary mysterious with the deft flick of a line or a sudden shift in tone. And his more recent collections, particularly Lifted (2005), are unashamedly more personal. We’ve featured my favorite Manhire poem, “Kevin” (from Lifted), here, and I’m also very fond of the ones below. If you like New Zealand accents (you weirdo), you can listen to him read “Hotel Emergencies” here.

Children

The likelihood is

the children will die

without you to help them do it.

It will be spring,

the light on the water,

or not.And though at present

they live together

they will not die together.

They will die one by one

and not think to call you:

they will be oldand you will be gone.

It will be spring,

or not. They may be crossing

the road,

not looking left,

not looking right,or may simply be afloat at evening

like clouds unable

to make repairs. That

one talks too much, that one

hardly at all: and they both enjoy

the light on the watermuch as we enjoy

the sense

of indefinite postponement. Yes

it’s a tall story but don’t you think

full of promise, and he’s just a kid

but watch him grow.* * *

My Sunshine

He sings you are my sunshine

and the skies are grey, she tries

to make him happy, things

just turn out that way.She’ll never know

how much he loves her

and yet he loves her so much

he might lay down his old guitar

and walk her home, musician

singing with the voice alone.Oh love is sweet and love is all, it’s

evening and the purple shadows fall

about the baby and the toddler

on the bed. It’s true he loves her

but he should have told her,

he should have, should have said.Foolish evening, boy with a foolish head.

He sighs like a flower above his instrument

and his sticky fingers stick. He fumbles

a simple chord progression,

then stares at the neck.

He never seems to learn his lesson.Here comes the rain. Oh if she were only

sweet sixteen and running from the room again,

and if he were a blackbird

he would whistle and sing

and he’d something

something something something.* * *

The News

A few survivors run for cover.

*

Each night at six we all go live to death.

there’s someone on the spot

to help me hold my breath.*

If I could just cry out

to my far, forgetful lover . . .*

or if you could only love me

oh World I am walking over.

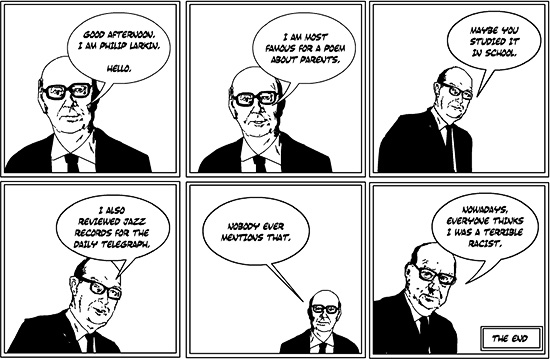

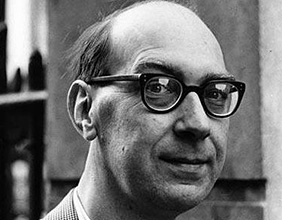

So, what to make of it all? Do we simply dismiss Larkin as a hateful racist? Or do we ignore the personal (“hey, he wasn’t as bad as Pound!”) and concentrate on the poetry? Motion writes that “the beautiful flower of art grows on a long stem out of often murky material,” and this kind of uneasy admission is perhaps the best we can do. And yet—it doesn’t seem quite enough to say “Okay, yes, Larkin was a bit of a racist; now here are some lovely poems!” Much of Larkin’s appeal comes from his ability to capture the oppressive, dreary pointlessness of life in a post-war England that has lost its faith—that is, ordinary life, lived by ordinary people. As poet X. J. Kennedy states in the New Criterion, Larkin gives us “a poetry from which even people who distrust poetry, most people, can take comfort and delight.” But who are these ordinary people Larkin writes for and about? If he’s racist, misogynistic, and a snob, are his “ordinary people” all middle-class white men? Is he writing for me, too? Do I really want to read a “deeply moving” poem by someone who perhaps suspects that significantly more than half the population is incapable (or undeserving?) of being moved? When I picture Kingsley Amis and Larkin writing sniggery, right-wing, posh-voiced bums to each other, I want to punch them both hard in their ruddy little noses. And yet—

So, what to make of it all? Do we simply dismiss Larkin as a hateful racist? Or do we ignore the personal (“hey, he wasn’t as bad as Pound!”) and concentrate on the poetry? Motion writes that “the beautiful flower of art grows on a long stem out of often murky material,” and this kind of uneasy admission is perhaps the best we can do. And yet—it doesn’t seem quite enough to say “Okay, yes, Larkin was a bit of a racist; now here are some lovely poems!” Much of Larkin’s appeal comes from his ability to capture the oppressive, dreary pointlessness of life in a post-war England that has lost its faith—that is, ordinary life, lived by ordinary people. As poet X. J. Kennedy states in the New Criterion, Larkin gives us “a poetry from which even people who distrust poetry, most people, can take comfort and delight.” But who are these ordinary people Larkin writes for and about? If he’s racist, misogynistic, and a snob, are his “ordinary people” all middle-class white men? Is he writing for me, too? Do I really want to read a “deeply moving” poem by someone who perhaps suspects that significantly more than half the population is incapable (or undeserving?) of being moved? When I picture Kingsley Amis and Larkin writing sniggery, right-wing, posh-voiced bums to each other, I want to punch them both hard in their ruddy little noses. And yet— Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odessa, former Soviet Union, in 1977. Although his early years were fairly peaceful (largely because his wealthy father was able to secure his family’s safety by bribing state officials), life in Odessa became increasingly difficult following the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1991. Political unrest, galloping inflation, and the outbreak of war in neighboring Moldova prompted the family to apply for political asylum in the United States. In 1993, the U.S. approved their application, and sixteen-year-old Ilya and his parents moved to Rochester, New York. Kaminsky’s father died the following year.

Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odessa, former Soviet Union, in 1977. Although his early years were fairly peaceful (largely because his wealthy father was able to secure his family’s safety by bribing state officials), life in Odessa became increasingly difficult following the dissolution of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in 1991. Political unrest, galloping inflation, and the outbreak of war in neighboring Moldova prompted the family to apply for political asylum in the United States. In 1993, the U.S. approved their application, and sixteen-year-old Ilya and his parents moved to Rochester, New York. Kaminsky’s father died the following year. Kaminsky’s first poetry collection,

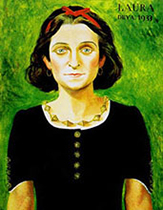

Kaminsky’s first poetry collection,  Laura Riding Jackson (1901-1991) was a renowned American poet, essayist, and critic. She was also a woman with a hell of a lot of names, and she could occupy any one of a number of spots in a Poetry A-Z series: she was born Laura Reichenthal; was first published under the name Laura Riding Gottschalk; subsequently dropped Gottschalk and went with Riding; and finally adopted Laura Riding Jackson as her authorial name from 1963 onwards. Since we’ve reached J in our poets’ alphabet, we’re going to go with Ms. Jackson.

Laura Riding Jackson (1901-1991) was a renowned American poet, essayist, and critic. She was also a woman with a hell of a lot of names, and she could occupy any one of a number of spots in a Poetry A-Z series: she was born Laura Reichenthal; was first published under the name Laura Riding Gottschalk; subsequently dropped Gottschalk and went with Riding; and finally adopted Laura Riding Jackson as her authorial name from 1963 onwards. Since we’ve reached J in our poets’ alphabet, we’re going to go with Ms. Jackson. In any case, it seems a little unfair that so many discussions about Jackson as a writer seem to become messy squabbles over whether she was a homewrecking control freak or a misunderstood (if pedantic) romantic. What matters is the work itself, and there’s no denying that during the first half of her life, Jackson wrote some of the most original, serious-minded poetry of the twentieth century. She was prolific, producing eleven volumes of poetry between 1926-1939, and highly regarded by many of her peers. Berryman hailed her as “the peer of any woman now writing poetry in English” and Auden called her “the only living philosophical poet.” In fact, Graves once wrote the young Auden a letter in which he reprimanded Auden for imitating Jackson’s style. For a taste of her best work, I recommend the series “

In any case, it seems a little unfair that so many discussions about Jackson as a writer seem to become messy squabbles over whether she was a homewrecking control freak or a misunderstood (if pedantic) romantic. What matters is the work itself, and there’s no denying that during the first half of her life, Jackson wrote some of the most original, serious-minded poetry of the twentieth century. She was prolific, producing eleven volumes of poetry between 1926-1939, and highly regarded by many of her peers. Berryman hailed her as “the peer of any woman now writing poetry in English” and Auden called her “the only living philosophical poet.” In fact, Graves once wrote the young Auden a letter in which he reprimanded Auden for imitating Jackson’s style. For a taste of her best work, I recommend the series “ I couldn’t think of a poet whose last name started with the letter I, so I asked google to help me out, and google said, hey, you silly sausage, how about Colette Inez? Nice job, google! (And if you’re reading this today, June 26th, please google the word gay and enjoy the

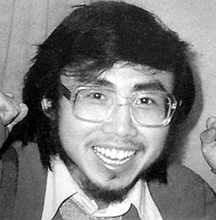

I couldn’t think of a poet whose last name started with the letter I, so I asked google to help me out, and google said, hey, you silly sausage, how about Colette Inez? Nice job, google! (And if you’re reading this today, June 26th, please google the word gay and enjoy the  Hai Zi is the pen name of poet Zha Haisheng, who was born to a peasant family in a rural Chinese province in 1964. A precocious child, Hai Zi was offered a place at the prestigious Peking University at the age of fifteen, and he graduated with a law degree four years later. He was shortly afterwards appointed professor at China University of Political Science and Law, where he edited the school’s journal and taught classes in aesthetics. It was while at university that Hai Zi decided to devote his energies to poetry. He read widely from classical and contemporary literature, and often sat at his desk working on a poem from dusk till dawn. During these productive years, he also began to exhibit signs of mental illness; he experienced hallucinations, and came to believe that certain people around him were intent on doing him harm. In March 1989, on or near his twenty-fifth birthday, Hai Zi committed suicide by lying down on a railroad track at the eastern end of the Great Wall.

Hai Zi is the pen name of poet Zha Haisheng, who was born to a peasant family in a rural Chinese province in 1964. A precocious child, Hai Zi was offered a place at the prestigious Peking University at the age of fifteen, and he graduated with a law degree four years later. He was shortly afterwards appointed professor at China University of Political Science and Law, where he edited the school’s journal and taught classes in aesthetics. It was while at university that Hai Zi decided to devote his energies to poetry. He read widely from classical and contemporary literature, and often sat at his desk working on a poem from dusk till dawn. During these productive years, he also began to exhibit signs of mental illness; he experienced hallucinations, and came to believe that certain people around him were intent on doing him harm. In March 1989, on or near his twenty-fifth birthday, Hai Zi committed suicide by lying down on a railroad track at the eastern end of the Great Wall. In 2010,

In 2010,