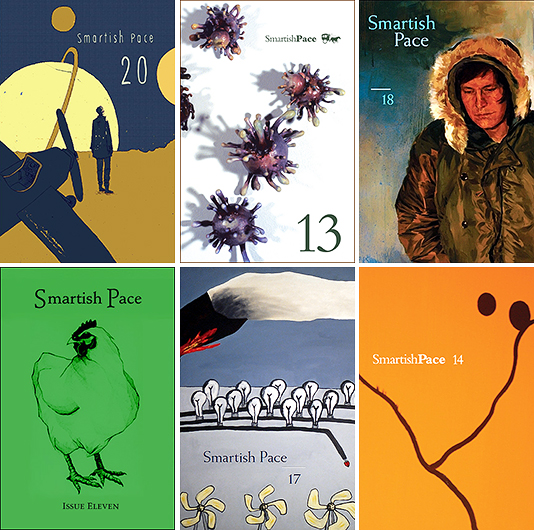

Yesterday we introduced you to the joys of Forklift, Ohio, one of the many literary journals you’ll be able to spill your latte on at Malvern Books (by the way, “you besmirch it, you buy it” is official store policy on days when we’re feeling cranky, so you might want to look into a lid). Today let’s take a peek at another cracking collectable, Smartish Pace.

Poetry journal Smartish Pace was founded by Stephen Reichert in 1999, while he was studying law at the University of Maryland. He named the journal for a nineteenth-century English legal case, Davies v. Mann, which involved an illegally parked donkey and a horse-drawn wagon traveling at a “smartish pace.” (It’s kind of an interesting case, actually, especially as it involves repeated use of the word ass: Davies, the plaintiff, had illegally tethered his ass at the side of a highway so it could graze. This sounds charmingly idyllic, apart from the highway part, but alas our defendant, Mann, galloped by in his horse-drawn wagon, struck Davies’ ass, and killed it. Davies was rather miffed by the loss and took Mann to court, arguing that even if his ass-tethering was a little naughty, Mann was also negligent in going so fast. And just so you know: the court ruled in favor of Davies and his deceased ass, and this ruling has led to the doctrine of “last clear chance,” which basically states that if you’re the last person who has a chance to prevent a disaster and you fail to do so, well, you’re in big trouble—even when said disaster was set in motion by someone else’s screw up.) Anyway! Enough about asses. More about journals. Smartish Pace is published annually, and it features wonderful poetry from new and established writers, including Pulitzer Prize-winning fancypants poets like Ted Kooser, Paul Muldoon, Maxine Kumin, and Mary Oliver.

Also worth nothing: Smartish Pace sells very cool t-shirts. We make a point of picking up a couple whenever we encounter the SP folks at a book fair. (Those SP folks know how to have a good time at a book fair; I suspect it involves whiskey.) And another excellent Smartish endeavor: their website features a Poets Q&A section—”the first interactive poetry forum on the internet”—where well-known poets like Rae Armantrout, Jorie Graham, and Robert Hass answer questions from readers. Here are a couple of responses from Robert Creeley:

How do you know when a poem is truly finished?

—Sue Kline, Lutherville, MDPerhaps you remember what Williams says in “The Desert Music”—it’s literally the text of an interview Mike Wallace did with him—and it goes something like, “Why/ does one want to write a poem?// Because it’s there to be written.” One knows a poem is finished when one comes to the end of that “writing,” when there’s no more to say or do, when whatever need and energies compelled and provided for it have gone. “Fled is that music…” It’s done.

What is the single greatest influence that Pound had on you as a person, and not necessarily as a poet—if that distinction can be made?

—Joel, ChicagoWhen he was still in St. Elizabeth’s, we had a very moving correspondence from my end—it was a complex of great Poundian maxims with sudden flashes of unexpected wit or playfulness. He’d sign his letters often: “Yours Anon/Y Mouse”—or he’d say, “You refer to something as being the case for the past forty years. Are you 24—or 64?” He used to address me as “Little Fish Basket”—terrific! Elsewise I’d be “the Creel”—and he gave me impeccable rules of thumb for paying attention, e.g., “Any tendency to abstract general statement is a greased slide…” or “Literacy is the ability to recognize the same idea in different formulations.” He quoted to me Aristotle’s “Swift perception of the relation between things is the hallmark of genius.” He taught me to take myself seriously as a writer (and person) and to learn how to work sans the usual frames of classroom or club. In short, he demonstrated that such writing as I hoped to do was serious, that it took concentration and practice, and that one had to keep engaged. As he says in the taped conversation with Geoffrey Bridson for the BBC, “You cannot have literature without curiosity.” One remembers it all.

Finally, here’s Reichert himself talking about the journal’s evolution in a digital age: