The Voynich manuscript is a fifteenth-century document consisting of 240 pages of very peculiar drawings and screeds of incomprehensible text. It comes from Europe, most likely northern Italy, and radiocarbon testing has established that the manuscript’s vellum dates from between 1404-1438. No one knows who wrote and illustrated the book; it takes its name from antiquarian Wilfrid Voynich, who rediscovered it in the library of a Jesuit college near Rome in 1912. Over the centuries the manuscript has had a number of documented owners, including Roman Emperor Rudolph II and a seventeenth-century Bohemian alchemist called Georg Baresch, but by the time Voynich found it, it had been missing for nearly 250 years.

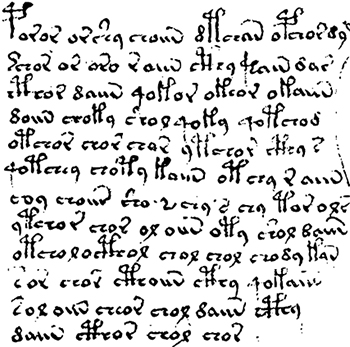

No one has ever been able to read the manuscript: the text does not match any known language, and scholars have never found any other instances of the script. Statistical analysis shows that the text has patterns similar to those of known languages, but there are some intriguing differences: for example, unlike most languages, “Voynichese” has very few two-letter words, and the words that appear most frequently are on the longer side (and yet, also unusually, there are no words longer than ten glyphs).

The inscrutability of the text has given rise to countless theories. Some scholars suggest the manuscript is written in code, but no one can determine what language it might be based on (Hebrew and Latin are popular contenders), and no one has ever been able to crack the code. Other Voynich boffins claim it’s a straightforward text written in a ‘lost’ language, with early Welsh and Nahuatl, a language of the Aztecs, being just two of the candidates. There’s also the possibility that the entire document is an elaborate prank—a sixteenth-century Sokal-type hoax designed to poke fun at the alchemical texts of the time. Finally, it wouldn’t be a properly spooky mystery without a few nutbars insisting on alien involvement.

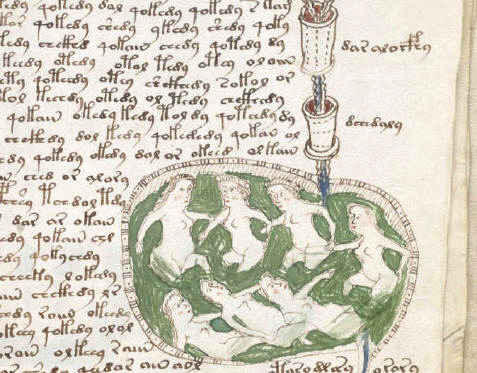

The artwork is as odd as the text. There are 113 drawings of unidentified plant species; numerous diagrams of a seemingly astronomical nature; and, most bizarrely, lots of sketches of little ladies, including “nude females emerging from pipes or chimneys” and “a biological section containing a myriad of drawings of miniature female nudes, most with swelled abdomens, immersed or wading in fluids and oddly interacting with interconnecting tubes and capsules.”

Yup. WEIRD. I love how so much of it looks so sensible. The plants look like plants that must surely exist… but they don’t. And the script looks so familiar—maybe if you squinted your eyes just so, it would all become utterly legible? And yet: TINY LADIES INTERACTING WITH TUBES.

Hmm. Your guess is as good as mine. A language lost to time? An impenetrable cipher? Or just some bored Renaissance prankster with a thing for botany and nudey pics? I’m going to bet my whimsical nickel on a Lost World theory—it’s an ancient Lonely Planet guide to some island that has long since sunk into the sea, an island where the flora was lush and the womenfolk liked to gallivant in giant tubs of green goop.

The original document is currently housed in Yale’s Beinecke Library, and the entire manuscript has been made available online. If you enjoy amateur cryptography—or just like looking at old pictures of plants and naked people—it’s well worth checking out.

And on a somewhat related note, if you like mysteries involving codes, one of the most compelling is Australia’s 1948 ‘Tamám shud’ case, which features an unidentified man found dead on an Adelaide beach with a cryptic message hidden in his pocket; the possibility of poison; a little Cold War intrigue; and a rare New Zealand copy of The Rubaiyat. There’s a fascinating account of the story here.