Once upon a time, in an art gallery full of foolish installations, I mistook a box on the wall containing a fire hose for some kind of interactive artsy doodad. I opened the box, an alarm went off, and a security guard appeared before me. He looked nervous. He told me that a disgruntled patron had recently hosed down one of the installations—modern art has that effect on some people—and now the fire hose box was alarmed and I was being alarming. “But I thought it was art!” I cried. “It’s a hose,” he said, and he escorted me from the room. I sat on a bench in the lobby and laughed and laughed until tears ran down my face and an old man sat down beside me and asked if I was okay. “Why are you crying?” he said. BECAUSE IT’S A HOSE.

The second time I cried in an art gallery, it was at the Whitney in 2010, and I was with my roommates. We’d gone to see something else—three young men dressed like vagrants, playing harps and shouting, maybe?—and after we’d had enough of that, we wandered through the rooms until we came across Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield.

The second time I cried in an art gallery, it was at the Whitney in 2010, and I was with my roommates. We’d gone to see something else—three young men dressed like vagrants, playing harps and shouting, maybe?—and after we’d had enough of that, we wandered through the rooms until we came across Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield.

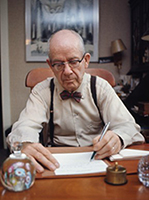

Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) was a quiet family man who spent much of his life in upstate New York. He painted watercolor landscapes, and he wrote in his journal, compulsively cataloging slants of light and mounds of snow, family card games and encounters with crows. In the gallery, the paintings and journal excerpts were displayed side by side, setting out for us an entire life.

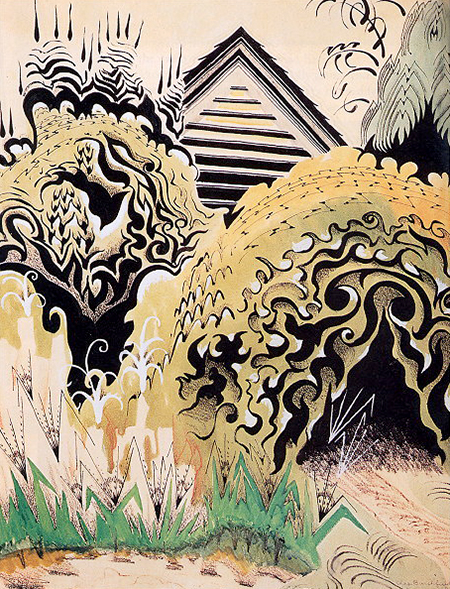

In youth, there is bravado, the promise of a great weirdness to come. And there is the beginning of Burchfield’s lifelong fascination with synesthesia, an obsession with painting sound as image—giving color and form to the chirps of crickets, the clanging of a train passing in the night, the howl of a dog in a distant yard.

On way to work. A great swooping wind out of the southwest. The tree tops roar against the cold gray sky; the clouds spit down a few wild flakes of snow now and then. Trees look blackly at the ground and the peaks and corners of the bleak houses are razor-sharp. I walk along exultantly with my chest out. All things are possible now. I felt like throwing a gauntlet into the face of the whole world; let me, like a winter wind, sweep all of the debris of the centuries away, I—alone—unaided!

In the middle years, there is comfort, complacency. Burchfield supported his family during the Depression by designing wallpaper and churning out conventionally pretty paintings of small town America—what one critic called “Edward Hopper on a dull November day.” He made his watercolors look like oil paintings; Life magazine named him one of America’s ten greatest painters.

I think that I am standing on the brink of an abyss of stagnant mire—or are my feet already sunken? The old serious attitude toward life seems gone—Life is easy—I am fat & healthy—my job flatters & pleases me—it presents no hardships—

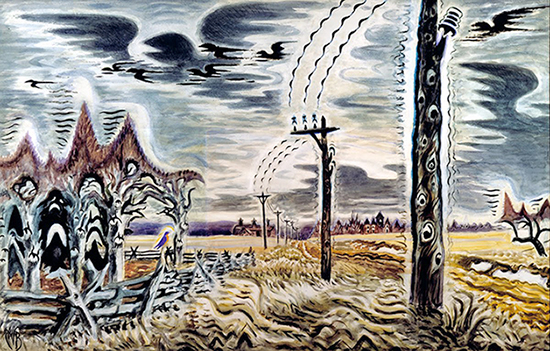

And then—the final years. Dissatisfaction; allusions to a psychological crisis. The years before are seen as a diversion, a squandering of obsession. In his later works, Burchfield returns to his early canvases and repurposes them, turning them into huge, hallucinatory paintings full of swirling strokes, exaggerated shapes, and an expressionistic light, a holy migraine shimmer. They perform a kind of trick, these paintings, translating an intensely private, mystical vision into shared experience: Edward Hopper painting scenes from Collective Unconscious Town. It’s a frightening place.

Spring in February: patches of melted snow on sidewalks reflecting the heavenly blue of the sky-cavern above, the snow on both sides of the walk honey-combed slantingly by the brilliant sun. The cawing of crows has taken on a new significance.

Growing stale is not so much in forgetting ideas but in losing the youthful vigour to consider them worth dying for—

A life set out on a few white walls: it made me cry. Endless snowfall, a thousand swirling birds. A cozy Christmas scene with the family. The sun painted as some blank horror that can never be looked at directly. You lose yourself in the middle of life—a dark wood, the path obscured, etc.—and when you find your way again, your youthful passions are like strangers to you. What was it you once cared about so much? The sound of a train passing in the night? A landscape that buzzes with the black hum of wires on a pole? The project is never completed.