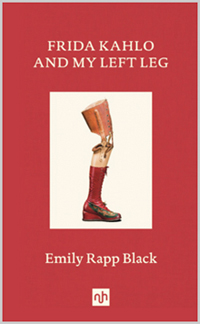

Frida Kahlo’s likeness appears on tote bags, t-shirts, mugs, refrigerator magnets, coffee table coasters and more; she has her own action figure. One of the most recognizable artists in the world, Kahlo symbolizes feminist strength, cultural pride, and the sharp essence of pain. In her poignant and deeply felt book Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, Emily Rapp Black interrogates the way in which Kahlo is reduced to a female artist whose muse is bodily and emotional suffering. Pain is not a muse, Rapp Black argues. “I do not believe that suffering was Frida’s main characteristic, because suffering does not create art, people do.” She adds that, yes, “[Frida] painted in bed. Create or die. That’s very different from ‘being inspired.’”

Frida Kahlo’s likeness appears on tote bags, t-shirts, mugs, refrigerator magnets, coffee table coasters and more; she has her own action figure. One of the most recognizable artists in the world, Kahlo symbolizes feminist strength, cultural pride, and the sharp essence of pain. In her poignant and deeply felt book Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, Emily Rapp Black interrogates the way in which Kahlo is reduced to a female artist whose muse is bodily and emotional suffering. Pain is not a muse, Rapp Black argues. “I do not believe that suffering was Frida’s main characteristic, because suffering does not create art, people do.” She adds that, yes, “[Frida] painted in bed. Create or die. That’s very different from ‘being inspired.’”

When Kahlo was six years old, polio disfigured her right foot. As a teenager, her spinal column, collarbone, ribs, pelvis, foot, and left shoulder were all broken or fractured in a streetcar accident. During her lifetime, she would undergo thirty-two operations. Due to gangrene, her leg was amputated. Rapp Black was four years old when her leg was amputated and she was fitted with a wooden leg. She writes, “Frida died on July 13, 1954; I was born twenty years later, almost to the day, on July 12, 1974. And yet our legs could have been made by the same man.” When she’s a twenty-one-year-old college student, Rapp Black discovers a translation of Kahlo’s journals and a deep cross-temporal friendship is born.

As a grown woman, Rapp Black visits Casa Azul, the home that Frida shared with Diego Rivera. She walks through the museum pregnant, “mostly belly,” remembering the questions she received, such as “Must you have a baby?” Perhaps these questioners did not know that Rapp Black had already had a baby, a little boy, who died at age three from Tay-Sachs disease. Throughout the book, the cruelty of able-bodied people is so palpable it stings. She writes, “The pregnant disabled body is one that mystifies onlookers….” Alongside other museum visitors, she views the narrow bed where Frida slept, made love, painted, convalesced, and died.

Rapp Black’s fierce protection of Frida is what makes this gorgeous book hum. In psychically protecting Frida from the ignorance of people who don’t understand disability, she is also, by extension, protecting herself, and the memory of her dead son. At the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, she overhears the conversation of two women, as they look at the various legs, casts, and corsets Frida wore. “Oh, these awful … devices. But it inspired her to paint,” one woman says. “Yes, it made her an artist. All that pain,” says the other. Rapp Black wants to shout at the women for reducing Frida’s existence to a narrative of pain. “Disability makes people uncomfortable” she writes; we neglect to see that “we will all someday live with a disability of some kind.” An artist cannot be captured by gift shop flair—not socks, or aprons, or stickers—and Rapp Black does a beautiful job of reminding us that Frida Kahlo’s “life was wholly vivid, saturated with all the things that make a life a life: knowledge of suffering; love; sex; friendship; home; travel; laughter; anger; joy; the creation of art.”