Celia recommends Fireflies in the Mist by Qurratulain Hyder:

Qurratulain Hyder occupies a strange place in literary history. Critics who know her work compare her with Gabriel García Márquez and Milan Kundera in the scope of her masterful imagination, and cite her as a precursor of Salman Rushdie in her fierce anti-colonialism. In 1989, she won India’s prestigious Jnanpith Award for Aakhir-e-Shab ke Hamsafar, translated in English as Fireflies in the Mist. Hyder translated her own work from Urdu—or, as she called it in reference to her magnum opus, Aag ka Darya (River of Fire, in English), she “transcreated” them, freely adding and subtracting passages, rewriting, and restructuring chapters. But, for all the praise that she received from those in the know, she hasn’t achieved the same place in the canon of world literature as many of her male contemporaries to whom she is most frequently compared. As I read Fireflies in the Mist, I wondered if there was not some bias at work here. For one thing, Urdu, despite its long and vibrant literary tradition, is not widely translated into English, and, like much Indian writing in translation, tends to be eclipsed by English-language novels from the subcontinent. For another, there’s the fact both the jacket copy and a number of English-language reviewers of Fireflies in the Mist seem to be under the truly puzzling impression that it is a love story—rather than a sprawling and incisive examination of women’s experiences in the Bengali independence movement.

Qurratulain Hyder occupies a strange place in literary history. Critics who know her work compare her with Gabriel García Márquez and Milan Kundera in the scope of her masterful imagination, and cite her as a precursor of Salman Rushdie in her fierce anti-colonialism. In 1989, she won India’s prestigious Jnanpith Award for Aakhir-e-Shab ke Hamsafar, translated in English as Fireflies in the Mist. Hyder translated her own work from Urdu—or, as she called it in reference to her magnum opus, Aag ka Darya (River of Fire, in English), she “transcreated” them, freely adding and subtracting passages, rewriting, and restructuring chapters. But, for all the praise that she received from those in the know, she hasn’t achieved the same place in the canon of world literature as many of her male contemporaries to whom she is most frequently compared. As I read Fireflies in the Mist, I wondered if there was not some bias at work here. For one thing, Urdu, despite its long and vibrant literary tradition, is not widely translated into English, and, like much Indian writing in translation, tends to be eclipsed by English-language novels from the subcontinent. For another, there’s the fact both the jacket copy and a number of English-language reviewers of Fireflies in the Mist seem to be under the truly puzzling impression that it is a love story—rather than a sprawling and incisive examination of women’s experiences in the Bengali independence movement.

A love story it is not, I am afraid—although there is love at work, romantic and familial, and marriage, and quite a bit about what happens after marriage, what makes it equal or unequal, successful or a failure. More than that, it is a story of the Quit India Movement in Bengal, its bravery and idealism, and also its disappointments and failures. Hyder’s erudite and lyrical writing draws on poetry, song, and dance from both English and Indian traditions, and her work deals with colonialism and its aftermath with both biting, clear-eyed anger and deep sadness. It is perhaps the most tragic bildungsroman I have read—the story of a generation’s attempt to make the society in which they lived anew, and of their dreams’ shortcomings.

At the novel’s beginning, the young women who will be its heroes are steeped in hope and idealism. All of them are budding communists, immersed in the Quit India movement, certain that the end of British colonial power will bring about a new era of justice, religious harmony, and social and economic equality. They make friends with each other across the lines of class and religion—Deepali Sarkar, the novel’s heroine, is a Hindu girl from an impoverished family, while her best friends, Rosie Bannerjee and Jehan Ara, are the daughter of a local Christian pastor and of a Muslim Nawab, respectively. For a while it seems like their bonds of friendship will be emblematic of the strength of the new political order. At this stage, the novel is full of exciting and slightly madcap adventures. Deepali dresses up as a veiled maidservant to spy on a British official and warn the local communist activists about upcoming police raids. She wins a scholarship to Santinekitan, the academy founded by Rabindranath Tagore, to study Indian classical music, and then fibs to her father about a student group collecting folk songs in order to travel to the Sunderbans to meet with another communist leader, the larger-than-life Rehan Ahmed, who crosses India disguised mostly as a wandering ascetic of various faiths—now “a gentle monk of Krishna,” now a Baul fakir who sings as he travels from house to house carrying secret messages.

Even at this point, however, there are clouds on the horizon. When Deepali carries a secret message to Uma Roy, a rich radical who has studied in England, Uma treats her with disdain, mocking her for her ignorance and suggesting that her political beliefs are mostly an excuse for her to chase boys. Deepali’s father, a doctor who runs a free clinic for the poor (and finds himself perpetually short of money as a result), lets her have her freedom, but Rosie and Jehan Ara’s families both disapprove of their political beliefs, and expect their daughters to be obedient, quiet, and to marry men that their families have chosen. For a while, the end of the British colonial regime looks like a path to a new kind of life for the three friends, encompassing not only racial and economic equality, but also new opportunities for women.

But even among their fellow radicals, there’s no consensus about what the place of women should be, just as there’s no real consensus about how far class equality should extend. Rehan Ahmed, the charismatic Marxist leader who falls in love with Deepali, idealizes his mother, who, having lost her fortune and married a man her uncle chose for her, spends her life serving her husband “in dutiful silence.” In his first love affair, he tries to convince his beloved to run away from her parents with him in the night, and, when she refuses, berates her: “If you do not have the guts to defy your autocratic father, how will you fight in the revolution alongside your comrade husband?” The idea that his would-be wife might simply be exchanging one type of autocracy for another does not occur to him.

The ending of Deepali’s love story, however, is comparatively bright. Her friends, Jehan Ara and Rosie, meet more chilling fates. Jehan Ara’s marriage is arranged by her parents, to a man they both know is a bad match for her. Rosie, in prison for her activism against the British government and abandoned by her family, meets a handsome lawyer with radical sympathies, who takes on her case and pays her bail. “I am going to take you home as my wife,” he tells her, the second time they meet. It’s not a question. She marries him. So each character must make her peace with a world that, in the end, is less revolutionary than she had hoped, and choose either to accommodate herself to society, or to rebel, and face the price: loss of stability, of a family, a home, a nation.

Towards the end of Fireflies in the Mist, there’s an image that begins to appear over and over: “Mother [Kali] sits in the marketplace of the world, flying her kites. She cuts off one of the millions of her strings and when the unattached kite flies, it reaches cosmic space. Mother claps her hands and laughs…” Is it an image of dissolution, or of freedom? There’s not much justice or resolution on display in Hyder’s novel, and what happiness there is, is as fleeting and fragile as those kites sailing into the void. There is, however, a new generation, who will carry on their parents’ and grandparents’ struggle—perhaps successfully, perhaps in vain. The novel’s original Urdu title, Aakhir-e-Shab ke Hamsafar, translates literally as “Fellow Travelers into the Night”—and, like fireflies, they seem to be so, groping out the shape of things in a world full of enclosing darkness and mystery.

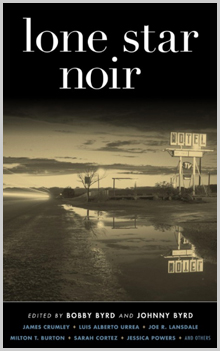

As editor Bobby Byrd so aptly states in his introduction to Lone Star Noir, “Texas, in all its many places, bleeds noir fiction.” From its hot and humid Gulf Coast to its isolated backroads country and its sprawling metropolises, Texas, with all its diversity, harbors endless possibilities for mystery. Published by New York-based

As editor Bobby Byrd so aptly states in his introduction to Lone Star Noir, “Texas, in all its many places, bleeds noir fiction.” From its hot and humid Gulf Coast to its isolated backroads country and its sprawling metropolises, Texas, with all its diversity, harbors endless possibilities for mystery. Published by New York-based  “Would it surprise you if I said that one day I transformed myself into a spider, a weeping willow, and a cyclamen flower?” Ahmed Bouanani asks somewhere in the middle of his novel The Hospital, translated this year by Lara Vergnaud and published by New Directions. “On the whole,” he continues, “we’re talking about a stolen life.” Like a prisoner who, shut inside four walls, invents his own world.

“Would it surprise you if I said that one day I transformed myself into a spider, a weeping willow, and a cyclamen flower?” Ahmed Bouanani asks somewhere in the middle of his novel The Hospital, translated this year by Lara Vergnaud and published by New Directions. “On the whole,” he continues, “we’re talking about a stolen life.” Like a prisoner who, shut inside four walls, invents his own world.