Stephanie recommends For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert by Mostafa Nissabouri:

Stephanie recommends For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert by Mostafa Nissabouri:

When Mostafa Nissabouri’s For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert (Otis Books, 2018) arrived here at Malvern Books, its title immediately gripped me; it’s quite a mouthful, with its seven words and their twelve syllables combining to create an unruly abstraction. The title tells us the book of poems to follow will likely be concerned with language in favor of what can’t be said. Sure, that’s one of poetry’s “jobs,” but to make that claim a part of the title struck me as bold, so I started opening to pages at random to gauge my further interest. And Reader, I had no chance; I’ve been reading and rereading Ineffable Metrics ever since.

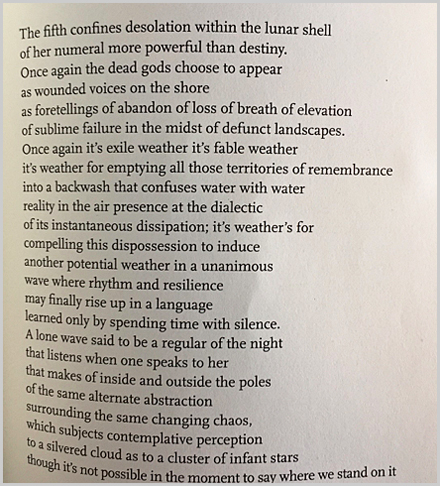

– from “Higher Memory,” translated by Pierre Joris

– from “Higher Memory,” translated by Pierre Joris

When I think about the experience of reading For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert—edited by Guy Bennett and featuring translations from French by Bennett, Pierre Joris, Addie Leak, and Teresa Villa-Ignacio—I think about: water; identities and how they are constructed; language as a landscape; land as conquered space; conquering as cyclical; how a poem might make a music of the tension between interiors and exteriors. And I think of specific excerpts I can’t (and don’t want to) shake:

“Dead I drink your water to know I’m separated from myself” (“Diurnal,” AL)

“what identity if not / imagined” (“Approach to the Desert Space,” GB)

“like a life possibility that is other like a cry” (“Anticipation of an Exclusion,” PJ)

“the absurdity of the infinite in my body / assassinated / humiliated / vampire” (“Scheherazade the Tongue,” AL)

“I don’t know where to put you / or how to forget and die” (“Scheherazade the Tongue,” AL)

But let’s go back to the beginning; the book’s first line is:

“Caves opened for the crawling of my ribs as if I were as if” (“Caves Opened,” AL)

What strikes me here is the repetition of “as if,” both because this is the first line of the book and so the “stutter” carries a particular weight and also because the line ends on that stutter, emphasizing that the speaker’s identity (or perhaps any identity) is indeterminate.

For Nissabouri’s speakers, identity is inherently fraught. Nissabouri was born in Casablanca in 1943, just roughly thirty years after Morocco was divided into French and Spanish protectorates. In his teen years, Nissabouri’s home regained its independence after almost half a century of French rule.

During those occupied years, Nissabouri says in an interview included at the book’s end, “young Moroccans in the north of the country were educated in Spanish and, in the rest of the country, in schools modeled on those of the French Republic and … in line with the programs of Jules Ferry. In these establishments Arabic was considered a foreign language. In Tangiers English predominated.”

Nissabouri continues: “So up to the end of the protectorate in 1956, we would see an entire population educated in francophone institutions … burst into professional life having been prepared to serve as assistants to the French colonizer … in the country’s administration. Everything was in French, from signs, bus routes, names of shops and their displays … The only Arabic press was in the north of the country, and that with the permission—under certain conditions, to be sure—of the Spanish who, unlike the French, didn’t care two hoots about a ‘civilizing mission.’ … Since then Morocco has opted for bilingualism (classical Arabic as its official language and French as its second language), except in the courts and related services where only Arabic is allowed.”

So why does Nissabouri compose his poems in French rather than Arabic?

“Vicissitude of history? Fatality? Intentional choice? Re-appropriation of the language of the other, the better to live my own status as one who narrowly escaped oblivion? It’s all of those things,” he says.

Or, perhaps, as the speaker of his poem “Approach to the Desert Space” says:

“it is not the sky that establishes order / its image overhanging a silenced memory does” (GB)

The poems in Ineffable Metrics are both dense and expansive. “Nissabouri’s work explodes across the page,” translator Addie Leak says (click on View Translator Notes), “questioning genre by breaking with traditional French forms and defying linguistic imperialism with long, syntactically complex sentences that include mid-phrase or mid-sentence erasures and insist that the reader work to pull sense from them.”

While I’m by no means a source of knowledge about Morocco, it seems fitting to me that—given the wonderful context provided by the notes and author interview included in this book—Nissabouri’s poems are concerned with the way space perpetually opens once conquered, whether it’s opening up new space for itself to reclaim an identity or culture after colonization or whether it’s having space opened within it by such colonization. And these are of course both violences, infinite ones:

“which is this nowhere whose desert / at my side is the shattered incidence / like an allegorical I / that never stops being multiple” (“Approach to the Desert Space,” GB).

When I sell this brilliant text to Malvern customers, I often talk about the trauma (that I imagine must be) involved when one’s country is in a way divided into different languages and then rule shifts so quickly; how it must feel to have something as intimate as one’s way of communicating determined to be Not the National Language or shoved underground or labeled appropriate only in the vernacular or appropriate only for religious ceremony, etc., and then to have those determinations change again. Of course what is a native tongue and what is a foreign language and what is a country and why do I speak English and on and on—I can’t possibly get into all of that here on this little bookstore blog, but my point in (stumbling through) bringing up such concerns is this: For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert, with its multiple tongues and diverse approaches to syntax, with its obsessions with “opposites” like desert and ocean, is a collection of poems rooted in such trauma. And Nissabouri’s language questions those roots, rips them from the ground, grows them into song.

I hope I’ve done this incredible work justice in this blog post; I had never before encountered Nissabouri’s poems and the book includes half of his published work and selections from current, unpublished work (including the astounding long poem “Seven Waves,” which I’ve not even touched on here!), so I found it particularly nerve-wracking to write about. But I wanted to write about it for two main reasons:

1) For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert is one of the best books of poetry published by a small press in 2018 and 2) I haven’t read a single review of the book or heard buzz in the English-reading book world about this critical English translation of such a singular poet. If you don’t want to miss out on this intelligent, wide-ranging work, stop by Malvern for your copy here in Austin or seek it out from your local independent bookstore.

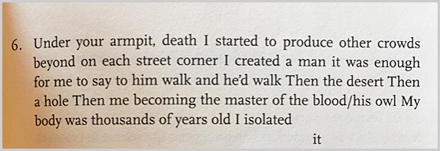

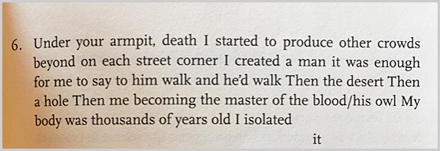

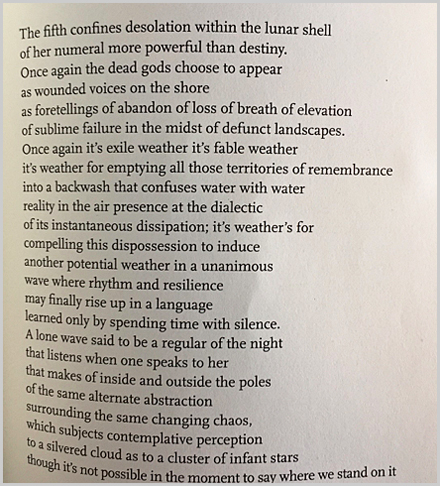

– from “Seven Waves,” translated by Teresa Villa-Ignacio

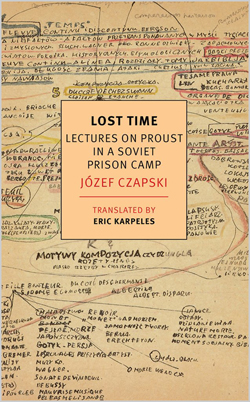

At the beginning of every year I ask myself, “Is this the year I will finally read Proust?” and by its end the answer is always no—however, I always enjoy reading about Proust. Polish artist and soldier Józef Czapski was a prisoner in a Soviet camp during the Second World War, and this book is based on two transcriptions of his lectures on In Search of Lost Time, which he delivered to his fellow inmates with only his memory to go on. It is a slim book, and I can vouch that it is very enriching for anybody interested in art, memory, Proust, World War II, and the power of literature.

At the beginning of every year I ask myself, “Is this the year I will finally read Proust?” and by its end the answer is always no—however, I always enjoy reading about Proust. Polish artist and soldier Józef Czapski was a prisoner in a Soviet camp during the Second World War, and this book is based on two transcriptions of his lectures on In Search of Lost Time, which he delivered to his fellow inmates with only his memory to go on. It is a slim book, and I can vouch that it is very enriching for anybody interested in art, memory, Proust, World War II, and the power of literature.

Stephanie recommends For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert by Mostafa Nissabouri:

Stephanie recommends For an Ineffable Metrics of the Desert by Mostafa Nissabouri: – from “Higher Memory,” translated by Pierre Joris

– from “Higher Memory,” translated by Pierre Joris

It’s easy to imagine Russell Page (1906-1985), author of The Education of a Gardener, holding his thumb up to a distant hill to assess where to plant a cluster of ancient lemon trees. Where a landscape painter is concerned primarily with light, Page must take into account the elements of sun, water, wind, soil, seasonal changes as well as sensory concerns: How might citrus aromas blend with nearby lavender and lilac? How might a box hedge in the background make the yellow fruit pop? Difficult to define—gardener, landscape architect, artist, sage, Page is all these and more. He is the creator of living breathing “pictures,” as he calls them, so that wherever you happen to stand, plants are in harmony with each other, with the landscape, and with you the observer.

It’s easy to imagine Russell Page (1906-1985), author of The Education of a Gardener, holding his thumb up to a distant hill to assess where to plant a cluster of ancient lemon trees. Where a landscape painter is concerned primarily with light, Page must take into account the elements of sun, water, wind, soil, seasonal changes as well as sensory concerns: How might citrus aromas blend with nearby lavender and lilac? How might a box hedge in the background make the yellow fruit pop? Difficult to define—gardener, landscape architect, artist, sage, Page is all these and more. He is the creator of living breathing “pictures,” as he calls them, so that wherever you happen to stand, plants are in harmony with each other, with the landscape, and with you the observer.