Rebekah recommends Hashish by Oscar A. H. Schmitz:

It has been a long time since a book has shocked and morbidly fascinated me as much as Hashish by Oscar A.H. Schmitz. Literary dandy Schmitz was held in high esteem by his contemporaries, but other decadent and fin de siècle writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Oscar Wilde have eclipsed his presence in modern mainstream consciousness. Thanks to Wakefield Press, however, this practically unknown collection of German tales has finally come out of the woodwork, available in English for the first time since its original 1902 publication. After a chance encounter with the alluring yet aging dandy Count Vittorio Alta-Carrara in a Parisian café, the narrator is invited along to a moody hashish club––red-tinged and candle-lit––where an eclectic assembly of travelers swap stories of extravagance, corruption, and debauchery. Alongside the Count and the narrator, the reader is swept up into a series of fantastical accounts of mistaken identity, Satanic rituals, and necrophilic love affairs. Gothic and grotesque, Schmitz’s novel delves into the dark and perverse undercurrents of dandyism, a lifestyle synonymous with refinement and elegance.

It has been a long time since a book has shocked and morbidly fascinated me as much as Hashish by Oscar A.H. Schmitz. Literary dandy Schmitz was held in high esteem by his contemporaries, but other decadent and fin de siècle writers like Edgar Allen Poe and Oscar Wilde have eclipsed his presence in modern mainstream consciousness. Thanks to Wakefield Press, however, this practically unknown collection of German tales has finally come out of the woodwork, available in English for the first time since its original 1902 publication. After a chance encounter with the alluring yet aging dandy Count Vittorio Alta-Carrara in a Parisian café, the narrator is invited along to a moody hashish club––red-tinged and candle-lit––where an eclectic assembly of travelers swap stories of extravagance, corruption, and debauchery. Alongside the Count and the narrator, the reader is swept up into a series of fantastical accounts of mistaken identity, Satanic rituals, and necrophilic love affairs. Gothic and grotesque, Schmitz’s novel delves into the dark and perverse undercurrents of dandyism, a lifestyle synonymous with refinement and elegance.

The novel, for a multitude of reasons, keeps the reader on their toes. But the aspect that generates the most uneasiness while reading it is the fact that it is virtually impossible to pin down its genre. Categorizing it simply as a work of decadent literature does not do Schmitz’s writing justice. Untethered from the constraints of reality and venturing headlong into the territory of the fantastic, Schmitz’s tales hover somewhere in between horror stories, surrealist literature, and hallucinatory drug writing. In “The Devil’s Lover,” a man is seduced by an older woman who, never allowing him to see her face, demands that their encounters always transpire under the cover of darkness. “A Night in the Eighteenth Century” details the deadly turn that a dinner party takes after the guests consume an unnamed herbal substance. The narrator himself appears in “Carnival,” where he learns a horrifying secret about a pair of sisters after sequentially sleeping with both of them. But “The Sin Against the Holy Ghost,” in which a corrupt priest attempts to sacrifice the soul of a fourteen-year-old girl in a satanic ritual, is the most disturbing of the tales by far.

Each episode is almost plausible––if it were not for the overly vibrant language, a reminder of the drug-induced state of both the storyteller and listener. Schmitz’s prose seems heightened, just like the hashish-users in the book who enjoy “a state of animated awareness.” Every background detail is luxuriously described, each of the five senses are magnified, and every word is imbued with a sumptuous richness. Take, for example, the narrator’s impression of the hashish club after ingesting the drug: “The dark red wallpaper glowed, as if the walls were made of glass behind which fabulous suns sank in great bursts of ember.” The settings and surroundings in each story take on a life of their own, portrayed in vivid technicolor.

The most mysterious, perplexing, and compelling character is the dandy Alta-Carrara, simultaneously attractive and unsettling. While noticing his unparalleled sense of style, particularly how a pair of narrow boots accentuate his legs, the narrator can’t help but comment on the abnormality of his “almost fleshless fingers” and how they tapered into “pointed, arch-shaped nails.” His beauty is unnerving, intriguing, and borderline grotesque––just like the tales themselves. He almost seems vampiric, impossibly flitting in and out of several of the stories, which span across centuries. Schmitz subtly weaves supernatural suggestions like this throughout the novel yet never confirms them. Whether an aftereffect of the hashish or truly a feature of some invented, alternate reality, the paranormal undertones are left uncertain, elevating the sense of uncomfortable fascination that characterizes the unique experience of reading this novel.

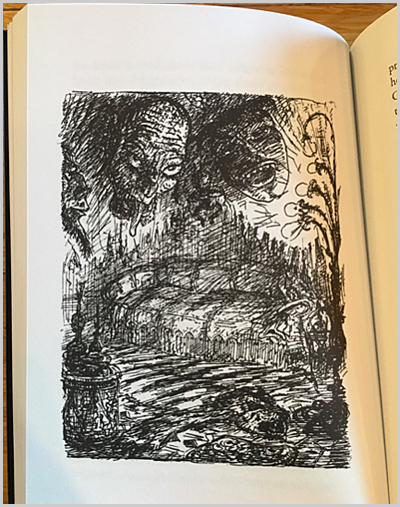

The haunting illustrations that accompany this 2018 edition are in part why the volume is so enchanting. Drawn by his brother-in-law Alfred Kubin, the black-and-white sketches, done in frenzied layers of pen ink, capture the chaotic nature of the stories themselves. Playing with deep shadows and white space, darkness and light, Kubin exaggerates the sinister qualities of the Gothic tales while contrasting with the colorfulness of Schmitz’s language.

The above drawing, my absolute favorite in the book, heightens the creepiness of the already-creepy “The Devil’s Lover.” Barring the demonic, snake-like face that immediately captures the eye, the image, upon further glance, is rife with hidden figures, barely illuminated by the haphazard light bulbs on the right-hand side of the page. And if you look close enough, the letters “S-A-T-A-N” are inscribed on the edge of the sofa, hardly visible among the shadowy upholstery.

Hashish is lurid and, frankly, sometimes disturbing. But it is simultaneously indulgent, beautifully written, and so imaginative that you won’t be able to look away. If you have ever wondered about what was merely hinted at in Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, what types of untold crimes Dorian might have committed during his trips to London’s opium dens, read Hashish.