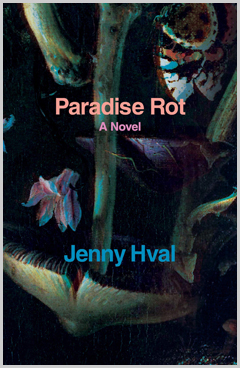

Celia recommends Paradise Rot by Jenny Hval:

There’s a girl, you see. She’s away from home, in another country, in fact, where she’s a foreigner, a student, staying at a hostel where the mirror is cracked and she doesn’t know anyone. Things are normal, but dislocated. It’s her first semester studying abroad. She has to find an apartment, she has to find friends. She has to navigate how she might feel about adulthood, about sexuality, about what it means to go out and exist in the world. Sometimes men walk up to her and inform her that she looks like a lesbian, which isn’t a thing she’s thought about properly, and the suggestion, coming from outside of herself, with its undertone of prurient sexual interest, makes it impossible to think about. There is a woman that she likes, but mostly she’s a friend. It’s not like that. Things aren’t what they look like.

There’s a girl, you see. She’s away from home, in another country, in fact, where she’s a foreigner, a student, staying at a hostel where the mirror is cracked and she doesn’t know anyone. Things are normal, but dislocated. It’s her first semester studying abroad. She has to find an apartment, she has to find friends. She has to navigate how she might feel about adulthood, about sexuality, about what it means to go out and exist in the world. Sometimes men walk up to her and inform her that she looks like a lesbian, which isn’t a thing she’s thought about properly, and the suggestion, coming from outside of herself, with its undertone of prurient sexual interest, makes it impossible to think about. There is a woman that she likes, but mostly she’s a friend. It’s not like that. Things aren’t what they look like.

It took me some time to warm up to Paradise Rot, the debut novel by Norwegian musician Jenny Hval. Here, it seemed, was a quiet novel, a meditation on longing and revulsion, about a young woman who’s far from home, and lonely. There are the small disappointments of being in a foreign country, without friends, watching the people around you appear to fit in effortlessly. It’s affecting, but quieter than I expected from Hval, in whose music even the quietest moments always feel like there’s something menacing and forceful under the surface.

But, as it happens, Paradise Rot undergoes a transformation as you read further into it. More than plot, the novel relies on a kind of cyclical recurrence of images in different contexts, in a way that felt, to me, almost more like a piece of installation art than a book. Maybe this is because the book is so much about the transformation of a particular space—the loft apartment in a converted brewery where Jo, the novel’s narrator, moves in with Carral, a lonely, beautiful girl to whom Jo feels an attraction that she can’t quite articulate. The loft has been hastily converted. It doesn’t really have walls, only thin cubicles of pasteboard, that don’t reach the ceiling and allow sound to carry.

It’s a setting that forces its inhabitants to continually negotiate the line between intimacy and disgust—Jo and Carral hear each other when they wake up early, when they pee, when they turn the pages of the book they’re reading. Carral rescues an enormous bag of heirloom apples that have been discarded by the local grocery—and then the women, faced with more fruit than they can eat, leave them around the apartment to rot, attracting spiders and flies and filling the loft with the smell of decomposition. Mushrooms begin to grow out of the thin pasteboard walls of the bathroom, where they’ve been warped by humidity.

Apples, mushrooms, the smell of rot, the sound of someone pissing in another room—there’s a cycle of disgust that propels the novel, each image reappearing and becoming stranger, more dangerous and also more alluring. Hval is interested in the nastiness of bodies, the potential for revulsion, and also the uncontrolled creativity that comes out of decay. This is a queer novel that’s interested in the ickiness of things, whether that’s falling in codependent love with a straight woman, or reading embarrassing romance novels (another reappearing motif is a pulpy romance that has, uh, two of its more salacious pages mysteriously stuck together), or experiencing a transcendent vision in which the object of your affection starts growing mushrooms out of her skin. Hval tightens the loop of the novel slowly, so that what feels real, by the end, is not the outer world that everyone can see, but the mysterious, frightening, closed world inside the apartment, where the walls are alive and boundaries between bodies are porous.