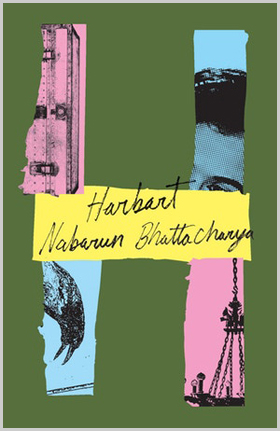

Celia recommends Harbart by Nabarun Bhattacharya:

Every ghost story is a story about how the past isn’t over yet. The murder that went unavenged is still felt, says the ghost, as is the last wish that went unfilled, the buried treasure left undiscovered, the inheritance that was stolen, the injustice that was covered up. Ghost stories insist that however much we might want to bury these things and leave them undisturbed, history returns, and insists on having its own say.

Every ghost story is a story about how the past isn’t over yet. The murder that went unavenged is still felt, says the ghost, as is the last wish that went unfilled, the buried treasure left undiscovered, the inheritance that was stolen, the injustice that was covered up. Ghost stories insist that however much we might want to bury these things and leave them undisturbed, history returns, and insists on having its own say.

And so the ghost story is a fitting medium for someone like Nabarun Bhattacharya, the son of radical artists Mahasweta Devi and Bijon Bhattacharya. Critics who have examined Bhattacharya’s novel Harbart, recently translated from Bengali into English by Sunandini Banerjee and released by New Directions, have often commented on the incongruousness of Bhattacharya, a radical and (for a while, at least) hardline Communist, writing about a hero who claims to possess the ability to act as a medium between the living and the dead. But Harbart is a phantasmagoric novel in which the messages the dead leave are lost, misinterpreted, and outright ignored. Realism, says Bhattacharya, is insufficient for a world in which the past is so evidently not finished with us.

Orphaned as a child, the novel’s hero, Harbart (his name is a Bengalicized version of the English Herbert), is relegated to a life as a dependent of his extended family. His adult cousin Dhanna lets him stay in his house but treats him as a servant, keeping him in a shack on the roof and instructing him not to use the indoor bathroom. Dhanna reasons that any generosity he shows his young cousin will only be met with an increase in Harbart’s expectations from him. He gripes when Harbart’s aunt gives the boy a present of secondhand clothing, and he turns a blind eye when his sons beat Harbart up.

Intelligent but lonely, Harbart soon drops out of school to spend his days with the neighborhood boys or alone in his room, reading about ghosts and murders. He lies to a neighborhood girl he admires that he’s studying with a private tutor, but in truth he’s trying to educate himself, piecemeal and ineffectively. There’s not much room in his life even for a childish flirtation: a teenaged friend who passes a note to a crush is cornered and repulsed by her family, and soon after he’s found dead in a city pond, apparently from suicide. Looking at his body as it’s retrieved from the water, Harbart imagines his friend “coming back as an obedient school of fish.”

It’s a life of compression, without family, purpose, friendship or love. The fear that makes Dhanna deny his cousin all but the most basic elements of life—give, and more will be asked of you—is the fear that animates society more broadly. Success requires connections, money, and preferably an English-medium education. Others are useful but expendable.

Life and death are cheap, until Harbart reinvents himself as a medium, whose job is to explain (for a substantial donation) that his customers’ loved ones passed easily and without pain into death, that they remember their family still, that they are happy, and that their final wishes will be simple to carry out. Faced with despair and grief, Harbart stalls for time or mouths platitudes: his job is to draw a curtain over the terror and absence of death, not to reveal it. This career has an unhappy ending: Bhattacharya makes it clear from the novel’s first chapter that Harbart’s career will end in attempted suicide.

Despite the banality of Harbart’s business as a medium, however, the novel does not dismiss him as a simple fraud. Rather, the dead live on among the living, occupying the same houses, the rooftop terraces and the corners, as if behind a pane of glass. But the messages they carry are too far from what those alive most want to hear. In his first such vision, Harbart sees the ghost of Binu, a cousin who was kind to him in his childhood—and who was murdered by the police for his Naxalite sympathies. Emerging from a mountain of crows, Binu whispers the location of the diary he hid from the police while alive. The crows around him fall down dead, bury him, and he waits enigmatically, moves through them as if through water, smiles.

The diary is where Binu says it will be. But no one reads it. The mystery, as far as the Sarkar family is concerned, is not Binu, not his thoughts or his long-ago plans, but what his appearance in Harbart’s dream means for Harbart’s future. Soon after Harbart goes out to purchase a sturdy sign for his new business: Conversations with the Dead. Prop: Harbart Sarkar. Binu’s grieving father, a staunch Communist who recites revolutionary poetry at his son’s cremation instead of a funeral prayer, leaves town, torn between his lifelong atheism and the apparent reality of the message that Harbart has delivered from his son.

The diary remains unread. This is a mistake. Harbart adores Binu. As a young boy, he waits outside his hospital room as his cousin lies dying, the door guarded by the police who killed him. He goes in to witness his last words. He carries messages and money to Binu’s Communist contacts in the city. He burns his cousin’s incriminating books. And then, terrified by the sudden violence of his cousin’s death, he forgets. Twenty years later, his ambition is only to gain enough respect from his family that he can move from his own squalid rooftop shack into Binu’s old room, and sleep on his cousin’s sturdy bed.

An orthodox radical would say this: the dead do not speak. So say the English-speaking members of the Bengali Rationalist Society, who visit Harbart’s business in order to debunk him, humiliating him in the process with his inability to speak English. Harbart churns out charming platitudes for them: such-and-such a relative was moderately virtuous, died with religion in their thoughts, and is now inhabiting a reasonable corner of Paradise. But the dead do speak, Bhattacharya insists: not in the voice of well-off, English-medium comfort and rest, but in mad laughter and convulsions of violence and rage at the return of the unjust, unforgotten, redressless past. Harbart is, in the end, the imperfect medium for a dead man’s plan, without knowing what he’s laid his own hands to.