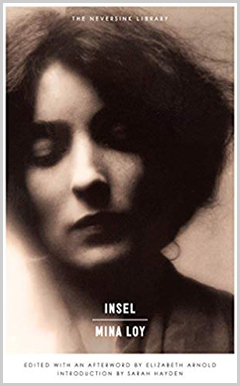

Celia recommends Insel by Mina Loy:

Mina Loy, of the many names! Most people who know her, I think, know her as a poet, for her volume Lunar Baedeckers. But she was also, by turns, an artist, novelist, designer, inventor of various practical and fanciful contraptions, and an intimate but aloof observer of just about any early twentieth-century avant-garde movement you’d care to name. Currently, I’m writing about her novel Insel, a self-contained segment of a larger autobiographical project, which was called “Islands in the Air” and deemed unpublishable in Loy’s lifetime.

Mina Loy, of the many names! Most people who know her, I think, know her as a poet, for her volume Lunar Baedeckers. But she was also, by turns, an artist, novelist, designer, inventor of various practical and fanciful contraptions, and an intimate but aloof observer of just about any early twentieth-century avant-garde movement you’d care to name. Currently, I’m writing about her novel Insel, a self-contained segment of a larger autobiographical project, which was called “Islands in the Air” and deemed unpublishable in Loy’s lifetime.

Insel is a fascinating prose experiment, marked by Loy’s poetic interest in the strangeness of language. Loy’s prose has one foot in academic jargon and the other in playground babble. She mixes French and German phrases liberally into her English, and, in high Surrealist fashion1, has great fun displacing words from their accepted contexts so that they sound strange and incomprehensible.2 She likes to insert a dependent clause in odd places, so that her twisty sentences have an element of the maze in them, leaving you to wander through them two or three times before you figure out where you’ve gone off course.

At the same time, Insel is a roman à clef about Loy’s friendship with the German painter Richard Oelze. The novel finds her—or rather, her heroine, Mrs. Jones—in Surrealist Paris in the early ‘30s, largely oblivious, as yet, to the war that hangs on the horizon, working as an art dealer for a gallery based in New York. Here she meets Insel, a feckless and impoverished painter who looks like a death’s head ravaged by black magic, who boasts loudly that he is starving to death, whose clothes are held together mostly by the dirt in their seams, and whose cadaverous and horrifying body sometimes dissolves, without warning, into an unearthly halo of psychic rays.3 Why is Mrs. Jones so drawn to him? Because he is more surreal than the Surrealists, because he seems to live in a waking dream, because despite her occasional disdain, they communicate on a psychic level at which mere personality disintegrates. Also, she’d have the reader know, she’s not drawn to him and she doesn’t like him. She merely admires his paintings, sort of, when he manages to work on them at all, which isn’t often.

An exile from Germany in 1933, Insel is, as Mrs. Jones puts it, “in a fix—for, in the ‘event’ being a German, here he was an enemy, whereas if he could return to Germany, there he was Kultur Bolshevik” (this is, remember, around the time the Nazis were purging so-called decadent artists).

Moreover, he’s destitute, and quite possibly in thrall to a morphine addiction.4 Despite the best efforts of Mrs. Jones and the Quaker charities of Paris, Insel is withering away in apparent starvation, looking ghastlier every time she sees him.

This is not to say that Insel is an object of pity. Despite the ethereal and visionary qualities that draw Mrs. Jones to him and the desperation of his poverty, he is also capable of a great deal of awfulness. When a girlfriend leaves him for another woman, he threatens to shoot them both—and, lest the reader find this threat unserious, he repeats the story for effect and gaily describes to Mrs. Jones how the two women hid together in their apartment for days while he waited outside on the street, so afraid were they that he’d make good on his threat. He gets into an argument with a black woman—maybe another lover, maybe a sex worker—in a café and slaps her across the face, to Mrs. Jones’s dismay.

Still, Mrs. Jones is largely untouched by his misogyny, protected by a kind of armor that might be that of her relative prosperity, her status as the collector who can get his art into the gallery or drop him, or might have to do with age. One friend of Insel’s, meeting her for the first time, is “appreciative until he discovered the hair in the shadow of my hat to be undeniably white— [whereon he] apologized with a shudder, ‘I won’t say it doesn’t look alright on you—but I can’t bear the sight. It reminds me that I am old.’” She recognizes that Insel frequently looks at her as if she were a sort of beefsteak, an amorous adventure rolled up with a nice wad of cash, but she doesn’t particularly care. Afflicted by the pain of “what turned out eventually to be a duodenal ulcer,” she lies down in his apartment and pretends to writhe in an agony of unrequited love for him. And oh, isn’t it funny, she seems to ask him, that you think this is the real thing?

And yet despite her determined refusal to empathize with his suffering, she is drawn to him. “Remember,” she tells herself sternly, “you don’t give a damn what happens to this thin man.” Then he gets an eviction notice, and she invites him to stay in her apartment while she’s at a country house. She is horrified when he takes her up on it, and then hurt when he never shows up after all.

Imagining him inhabiting her apartment, she works herself into a terror that she might have accidentally switched a bottle of gin with some leftover bleach in a gin bottle, and admonishes Insel, by telegram, to please drink absolutely nothing out of any kind of bottle in her house. It’s lost on absolutely no one that the root of this anxiety about poison is really that she’s worried Insel might be making himself at home in her house, touching her glassware, and, despite having invited him, she’d prefer it if he didn’t. Before letting him into the house, she’s collected all her papers out of her drawers, sewn them up in a kind of body bag contraption made out of an old and voluminous painting apron, and locked them alone in a spare room, where they lie like an inert and wordy Mrs. Rochester. They’re an uncomfortable pair, these two—Insel with his barely-restrained hunger and disdain for women, and Mrs. Jones, whose experiences of psychic transcendence are tempered by the protection of her money, and her almost touristic curiosity about the squalor of Insel’s life.

At this point, one could be forgiven for thinking that what we’re dealing with here is basically a realist novel set in the milieu of the Surrealists, but if I leave you with that impression I will have done a terrible job of describing exactly what is so strange and marvelous about this book. The realist concerns of setting and character, here, are to a great extent only the undercurrent beneath Loy’s greater concern, which is the lived experience of Surrealism and psychic derangement, and how to express these uneasy experiences of art within the framework of a quotidian, chance relationship. Like Breton’s Nadja, Insel provides Mrs. Jones with an opportunity for what she calls “psychic research”—a term whose suggestions of voyeurism and power struggle Loy treats with rather more self-awareness than Breton.

While their early meetings are marked only by a weird synchronicity and Mrs. Jone’s indefinable sense of a shrouding black magic, as their friendship continues, strange things begin to happen. First of all, there is Mrs. Jones’s consciousness of Insel’s rays, or Strahlen, as she says in German (Insel is proficient in neither French nor English, and they speak to each other in a mishmash of languages), which emanate from him at odd moments, with such force that they erase his skeletal, dirty body. Or there is the day that, after spending a night drinking with Insel, Mrs. Jones is walking down the street and finds that “… I was cleft in half. Like the witch’s cat when cut apart running in opposite directions, suddenly my left leg began to dance off on its own.” Insel’s eyes become oysters swimming in strange constellations. His arms extend to fantastic lengths. He is a sick clochard, perhaps sick unto death, he is a mean and sadistic piece of work, but he’s also held together by some force of psychic power which fascinates Mrs. Jones, and without which she suspects he would simply fall apart into his component pieces.

Near the end of their relationship, Mrs. Jones confronts Insel, longing to tell him this: “I have absorbed all of your Strahlen. Now what are you going to do?” As if she might be able, truly, to vampirize him and absorb his madness and the enormous wasted potential of his art. No sooner has she thought it than she must admit that it isn’t true. She’s been an observer. And now she has seen enough.

- To be clear: Loy did not self-identify as a Surrealist, having too little patience for the fussy hierarchies that André Breton liked to impose on his followers. Mrs. Jones, the narrator of Insel, frequently pauses to mock the Surrealists for not, as it were, practicing what they preached.

- A certain cast of light, for instance, is penetrant, a word which, with its aural echo of penitent, I was sure that Loy had simply invented, but which turns out to mean, variously, “a compound that penetrates the skin, as in a lotion,” “a substance that lowers the surface tension of water,” and “a large nematocyst discharging a barbed thread that penetrates the body of its prey and injects a toxic fluid,” in addition to being a banal synonym for penetrating.

- Yes, psychic rays. We’ll get back to that.

- Mrs. Jones hears this rumor about his morphine use only some time into her acquaintance with Insel, and prefers to erase it from her memory, even as the money that she and other friends loan Insel consistently disappears into the ether, and he looks more and more ill. Loy herself was rumored to have helped Oelze quit his own morphine addiction, and there’s some evidence that she erased references to drug use from successive editions of the manuscript of Insel. A separate novel fragment, appended to this edition, describes him rather lovingly as “my drug addict.”