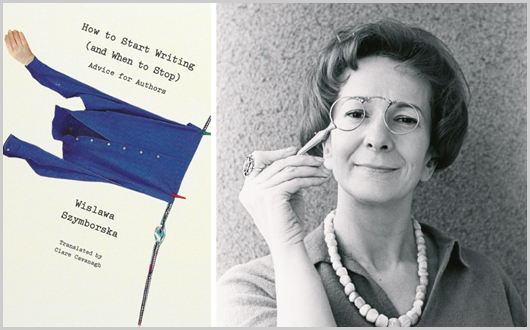

How to Start Writing (and When to Stop): Advice for Authors by Wisława Szymborska, translated from the Polish by Clare Cavanagh

by JP Poole

When it comes to crushing a writer’s literary aspirations, Wisława Szymborska is a skilled practitioner; when she brings the hammer down it lands with a clang and stylistic flair.

In 1968, Szymborska and another novelist started the Literary Mailbox, an advice column published in the Krakow-based journal Literary Life. Letters from novice writers poured in. Not wanting to reveal her gender, Szymborska responded in the first person plural. How to Start Writing (and When to Stop): Advice for Authors, translated by Clare Cavanagh, is a wicked, laugh-out-loud read. The slender book also includes Szymborska’s collages, which add another layer of insight into the Nobel Laureate’s keen imagination.

Readers are left to fill-in-the-blank as to the sort of letters and submissions piled on Szymborska’s desk. The book is composed of only her replies. Her comments are so pointed and brilliant that it is entirely possible that some people wrote in just to receive a delicious sting.

In response to one writer, R.S., from Olsztyn:

You dream of getting a typewriter; you think it would make your writing better. This is not essential. Your plan for typing out poems en masse troubles us.

In another response she writes:

To Roland, from the Lublin Province

The problem of life’s absurdity is not addressed by rhyming “bottomless” and “sarcophagus.”

Even her “encouraging words” are evidence of a poet who has read everything and will not be tricked by imitators.

To Zegota, from Bialystok

If we take this, please pass along Oscar Wilde’s current address so we can send him the lion’s share of the honorarium.

Szymborska tells a few budding young writers that perhaps they should concentrate their efforts on living life until their brains mature; it might seem a bitter dose of medicine, but I found it sound—probably advice I should have taken as a pimple-faced goth, noodling with end rhyme.

She tells people not to torture themselves to become creative geniuses; poetry is a calling, and those who are called won’t stop at the first sign of rejection. She admits her first poems and stories were absolute rot, but she has little patience for those who expect to be showered with praise after penning their first batch of poems. Her advice to one writer is to keep his pages in a drawer and don’t let them out again.

What Szymborska reminds us is that there are no short cuts. (Or if there are they’re called ghost writers.) And she believes wholeheartedly in talent and isn’t afraid to say that some have it, some don’t. That’s not the end of the world either. The next tech genius might be wasting her time forcing her lump of novel into a saleable rectangle when her time would be better spent revolutionizing the web. “Curiosity is the key to existence,” she writes. That applies to poets as much as it does to those better suited to pastry making, engineering, or animal husbandry.