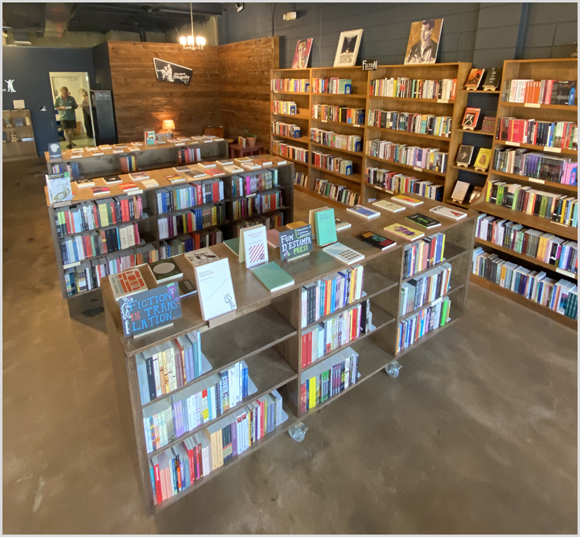

We’re delighted to bring you some excellent news: our former brick-and-mortar home at 613 West 29th Street is now the location of a wonderful new bookstore, Alienated Majesty. We spoke with the store’s owners, José and Melynda, to find out more about their exciting literary venture…

Alienated Majesty is a memorable name… where does it come from?

José thought of it! It comes from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay “Self Reliance”: “in every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts; they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” We liked the optimistic feel of the quote. We hope that readers will find their own ideas in our books returning to them in interesting and innovative ways.

We also liked the idea of making visual jokes with space aliens and royalty, so you’ll occasionally see those in the store.

Tell us a little bit about the people behind the store—has bookselling been a longterm dream? What’s your background?

Honestly, we never thought of opening a bookstore until Malvern closed. Like a lot of people we paid a few final visits once we heard the store was closing, and we started to realize how much having a place like this meant to the city and the literary community. Our friends encouraged us to keep it going, so we took the plunge.

But both José (Skinner) and Melynda (Nuss) have spent a lifetime around books. José started writing dispatches from Nicaragua and El Salvador in the 1980’s. He has since graduated from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and co-founded and directed the Creative Writing M.F.A. at the University of Texas Pan American (now UT-RGV). He is the author of two collections of short stories, Flight and The Tombstone Race, and a forthcoming novel, The Search Committee.

Melynda has a PhD in English from UT Austin and taught literature at UT-RGV for over a decade. She is also a lawyer, and after she retired from teaching she started a small law practice to help writers with their copyrights and contracts. It was through her clients that she learned what a vibrant role small independent presses play in introducing new authors to the literary scene. She wanted to make those books more available to readers.

What is the mission of Alienated Majesty?

We want to provide a place where the readers of Austin can come to discover authors that they might not find at other bookstores. We focus on works published by small, independent presses—though we will carry a few large press books if we think they will appeal to our readership. We also plan to carry a large number of works translated from other languages. I was amazed to find that only about 3% of books sold in America were translated from other languages. No wonder Americans have trouble understanding the rest of the world! Readers who shop at Alienated Majesty will discover poetry, fiction and non-fiction from all over the globe.

What have been some challenges in setting up the store?

It seems like there’s a new challenge every day! Probably our biggest challenge was figuring out how we could efficiently heat and cool the space. There was no insulation, and this summer the metal ceiling felt like an oven! So just as we were starting to receive books we had to cover everything up and install some spray foam insulation. It was a mess, but now the space is much more comfortable and our electric bills are a lot lower. We’ve also had a few misplaced orders, some shipping problems. It feels like it’s been years since we started this venture when really it’s only been a few months.

What do you envision for your community of readers, e.g. will you host events?

We have some really exciting things planned! We’ll have plenty of readings and other opportunities for authors to present their work. We’re also hosting a few reading groups. But C. Rees, our event coordinator, is also exploring other kinds of events. We’re thinking of group readings, presentations on the craft and business of writing, interviews with authors and publishers, pop-up stores, musical events, lit-crawl type games—any event that will delight our customers and help inform them about the books we carry. We want to engage the communities in Austin who loved Malvern Books, as well as expand to include those who weren’t lucky enough to go there.

Right now we’re working on a grand opening weekend sometime in late September or early October, where we’ll invite authors who read at Malvern to help us christen the new space—along with a few other surprises. Readers can sign up for our mailing list—or follow us on Instagram or Facebook—to get the details when they’re announced.

What’s something that new customers might find surprising about the store?

We’ve managed to pack a lot more books into the space! We commissioned some bookcases on wheels that we can move out of the way for readings and events, and they’ve really allowed us to expand the number of books we carry. We’ve added comics and graphic novels and a larger non-fiction section. We also have a sofa and some comfy chairs where readers can check out their purchases.

We’ve heard that customers might bump into some former Malvernians while they’re shopping, is that true?

Yes! Stephen Krause has been working with us to make sure we have all the books Malvern readers love, and author Fernando Flores has also been helping us set up the store. We had a few regular Malvern customers knock on our door even before we opened—and lots more come to our soft opening on August 15th! We hope everyone who loved Malvern will find a home here.

You had your soft opening recently—how did it go? And what are your plans for your Grand Opening?

We opened our doors for the first time on August 15th—ready or not! We didn’t circulate the news widely because we were still missing a few major orders. But people still found us, and we had a great day. We will probably still be unpacking boxes for a few weeks. We hope readers don’t mind the mess! But we have some great books in, and we know people are ready to have them. It should be a fun—if chaotic—time.

We’re planning the real Grand Opening celebration for sometime in late September or early October, when the weather is cooler and students and faculty are back in town. We’re going to have a full weekend of readings and community events. I can’t tell you everything now; we’re still firming up the details. But we’ll announce the full lineup on our email and social media when it’s ready.

Where can people find you online? Do you have a link where people can sign up for newsletters?

Our website: alienatedmajestybooks.com. There’s a link on that page where readers can sign up for our mailing list. Readers can also follow us on Facebook and Instagram.

What are you reading at the moment?

Melynda is reading Peach Blossom Paradise by Ge Fei. It’s an NYRB classic, translated by local Austin translator Canaan Morse. It’s set in turn-of-the-century China, where revolutionaries are challenging the structures of the ancient Chinese empire, and it follows a young girl, Xiumi, as she travels the unlikely road from privileged daughter to revolutionary leader. Along the way, she sees teachers, revolutionaries and bandits trying to build their communities into paradise. I haven’t quite finished, and I can’t wait to see how it turns out.

José is reading Modelo antiguo by Luis Eduardo Reyes, a satire of the Mexico City he remembers from his college days there.

Anything else you’d like to mention?

We are so grateful for all the help we’ve received from the Malvern community! The Bratcher estate gifted us with the bookcases and displays, and Becky gave us lots of good advice. Stephen has been instrumental in helping us get the store set up. And we’ve received so many nice comments from readers who loved Malvern. Joe Bratcher really built something special.

We wish José, Melynda, and Alienated Majesty all the best, and hope y’all will enjoy visiting the store and supporting this wonderful new addition to Austin’s vibrant literary community!

I was first drawn to this slim, unassuming novel by its title—what on earth is a post horn, I wondered, and why should we rejoice in its longevity? The source of the title is given in the epigraph—it’s a quote from Constantin Constantius, the narrator in Kierkegaard’s Repetition: A Venture in Experimental Psychology:

I was first drawn to this slim, unassuming novel by its title—what on earth is a post horn, I wondered, and why should we rejoice in its longevity? The source of the title is given in the epigraph—it’s a quote from Constantin Constantius, the narrator in Kierkegaard’s Repetition: A Venture in Experimental Psychology: Hjorth is a highly regarded novelist in Norway; she has written more than twenty novels, and her second English-translated novel, the putatively fictional family saga Will and Testament, won the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature. Will and Testament was also highly controversial. The novel’s protagonist, Bergljot, shares many conspicuous similarities with Hjorth, and in the novel Bergljot claims that her father sexually abused her when she was a child. Hjorth’s younger sister Helga condemned the book as lies, and in 2017 she published her own novel, Free Will, in which a family is torn apart by false allegations of incest. For her part, Hjorth insists Will and Testament is not autobiographical.

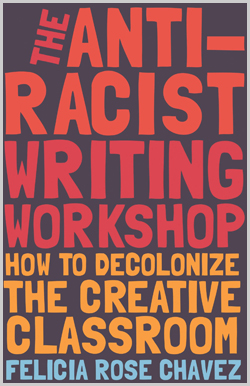

Hjorth is a highly regarded novelist in Norway; she has written more than twenty novels, and her second English-translated novel, the putatively fictional family saga Will and Testament, won the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature. Will and Testament was also highly controversial. The novel’s protagonist, Bergljot, shares many conspicuous similarities with Hjorth, and in the novel Bergljot claims that her father sexually abused her when she was a child. Hjorth’s younger sister Helga condemned the book as lies, and in 2017 she published her own novel, Free Will, in which a family is torn apart by false allegations of incest. For her part, Hjorth insists Will and Testament is not autobiographical. “Silencing writers is central to the traditional writing workshop model,” Chavez writes; it dates back to 1936, when Iowa became the first degree-granting program for writing. With primarily white faculty, students, and reading list, the workshop has long been a space for “safeguarding whiteness as the essence of literary integrity.”

“Silencing writers is central to the traditional writing workshop model,” Chavez writes; it dates back to 1936, when Iowa became the first degree-granting program for writing. With primarily white faculty, students, and reading list, the workshop has long been a space for “safeguarding whiteness as the essence of literary integrity.” Guillermo Rosales’s The Halfway House is a brilliant and stark portrait of what it’s like to live in multiple rings of exile, not unlike Dante’s multiple rings of hell. When the novel’s protagonist, William Figueras, arrives in Miami, his relatives expect to embrace a young Cuban exile ready to make it big in America. Instead, they lock eyes with someone they barely recognize—a rail thin stranger who hurls insults at them through missing teeth and is suffering from paranoia. Figueras is admitted to a psychiatric ward that day. He escapes Cuba only to enter the U.S. and be exiled again to the broken mental health care system, ending up in a privately-run halfway house that’s one tier better than living on the streets.

Guillermo Rosales’s The Halfway House is a brilliant and stark portrait of what it’s like to live in multiple rings of exile, not unlike Dante’s multiple rings of hell. When the novel’s protagonist, William Figueras, arrives in Miami, his relatives expect to embrace a young Cuban exile ready to make it big in America. Instead, they lock eyes with someone they barely recognize—a rail thin stranger who hurls insults at them through missing teeth and is suffering from paranoia. Figueras is admitted to a psychiatric ward that day. He escapes Cuba only to enter the U.S. and be exiled again to the broken mental health care system, ending up in a privately-run halfway house that’s one tier better than living on the streets.