Long Live the Post Horn! by Vigdis Hjorth, translated by Charlotte Barslund

I was first drawn to this slim, unassuming novel by its title—what on earth is a post horn, I wondered, and why should we rejoice in its longevity? The source of the title is given in the epigraph—it’s a quote from Constantin Constantius, the narrator in Kierkegaard’s Repetition: A Venture in Experimental Psychology:

I was first drawn to this slim, unassuming novel by its title—what on earth is a post horn, I wondered, and why should we rejoice in its longevity? The source of the title is given in the epigraph—it’s a quote from Constantin Constantius, the narrator in Kierkegaard’s Repetition: A Venture in Experimental Psychology:

Long live the post horn! It’s my instrument for many reasons, principally because you can never be sure to coax the same tone from it twice; a post horn is capable of producing an infinite number of possibilities, and he who puts his lips to it and invests his wisdom in it will never be guilty of repetition…

A little googling reveals that a “post horn” is “a valveless horn used originally to signal the arrival or departure of a mounted courier or mail coach,” and all becomes clear when we realize that the plot of this novel centers on an obscure piece of postal-political history: in 2011, the European Union issued a directive that the Norwegian postal service must open up competition for the delivery of letters that weigh less than 50 grams. Fearing that this move would cost many postal workers their jobs, Postkom, the Norwegian Post and Communications Union, set out to fight the directive—and in Long Live the Post Horn!, this spirited fight against free-market mail is fictionalized, and conducted with the help of our narrator, Ellinor, an apathetic 35-year-old media consultant. Ellinor has a boyfriend she seldom thinks about and a mother and sister whose troubles don’t seem to trouble her; she takes no interest in what she calls their “tiny lives.” Ellinor is depressed, and her depression has left her affectless, lethargic. Looking out over the Oslo Fjord, gloomy inspiration for Edvard Munch’s “The Scream,” Ellinor can barely muster a whimper: “It wasn’t nature screaming, nature was cool and numb, remote and inaccessible, it was me screaming a non-scream.”

Adventures in postal union politics might sound too prosaic a topic for a page-turner, but renowned Norwegian novelist Vigdis Hjorth raises the stakes from the very beginning, introducing us to Ellinor’s existential crisis in the book’s first paragraph:

As I was putting away in my basement lock-up some saucepans that couldn’t be used with my new induction hob, I came across an old diary from 2000. The diary had been a Christmas present and I had written in it for a few months before I got bored…. I opened it and began reading; I had made entries almost every day from 1 January to 16 May. When I had finished, I felt so sickened I couldn’t sleep. I got up and opened a window to let in some air. I drank some water and paced up and down the living room before I went back to bed and opened the diary again as if hoping something had changed. January’s entries were about the winter sales and some guy named Per I thought might be interested in me. In February it was a guy called Tor and a Mulberry bag I’d managed to get half-price and a pair of shoes I should have bought half a size bigger…. The names were interchangeable, as were the dates, there was no sense of progression, no coherence, no joy, only frustration; shopping, sunbathing, gossiping, eating—I might as well have written ‘she’ instead of ‘I.’ And had anything changed, had growing older made any difference?

Days later, with the unchanging pointlessness of existence still spinning in her head, Ellinor receives some startling news: her colleague and mentor at their three-person publicity firm has disappeared (and is later discovered to have taken his own life), and Ellinor and her remaining colleague Rolf must take over the postal union’s publicity account.

Rolf is convinced the project is doomed from the start—they’ll never succeed in persuading Norway’s ruling party to oppose the EU’s directive—but Ellinor finds herself ever so slowly starting to care about the fate of the postal workers. She commits to listening to and understanding their concerns. She even goes so far as to visit the distant home of Rudolf Karena Hansen, a devoted mailman who delivers to isolated homes beyond the Arctic Circle. He explains to her the importance of delivering “dead letters,” letters without a clear name or address, and offers her life advice:

“If you want an easy life,” he said, “all you have to do is make yourself insignificant. Believe in one thing today, another tomorrow and something completely different by the end of the week, turn yourself into several people and parcel yourself out, have one anonymous opinion and another in your own name, one spoken, one written, one on the Internet, another in the shop and a third as a lover, yet another as a PR consultant, or as a private individual and another with Postkom, and then all your trouble will go away, you’ll see.” I closed my eyes, but to no avail, I started to cry.

As she works to save the postal service, Ellinor begins to emerge from the fog of apathy. She mails her boyfriend a love letter, feels herself feeling for the first time in a long time:

Spring had to be the reason. March and the light in March and a few coltsfoot shoots on the verges. Tender new trees that looked as if their keen, green leaves made them bashful, the older trees stood guard, the birds flew between them with twigs in their beaks, building nests for which they needed no planning permission … We were pensive at the office and opened the windows when the sun was high in the sky and heard the birds chirping and free. We’ve put on our thinking caps, we would say when we bumped into each other in the corridor or in the kitchen after having sat for a long time at our respective desks hunched over foreign newspapers and magazines trying to understand the EU, EFTA and neoliberalism. It’s not all bad to have to put my thinking cap on again, Rolf said, and I knew what he meant, we were on the right track. We learned and understood and tried to think new thoughts, it was a blessed relief and although we became increasingly conscious of our impotence, at least we were no longer lying to ourselves.

It seems impossible that a novel about the minutiae of postal politics could be this gripping, and yet, thanks to Hjorth’s ability to merge wry detachment with yearning idealism, I found myself caring deeply about the fate of Ellinor—and the Norwegian postal service. (Spoiler alert: the real-life fate of the EU’s postal directive can be found here, should you also find yourself invested in Scandi mail drama.) Hjorth’s spare, rhythmic prose and understated humor are perfectly suited to this droll yet life-affirming account of a woman teetering between despair and revolution.

Hjorth is a highly regarded novelist in Norway; she has written more than twenty novels, and her second English-translated novel, the putatively fictional family saga Will and Testament, won the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature. Will and Testament was also highly controversial. The novel’s protagonist, Bergljot, shares many conspicuous similarities with Hjorth, and in the novel Bergljot claims that her father sexually abused her when she was a child. Hjorth’s younger sister Helga condemned the book as lies, and in 2017 she published her own novel, Free Will, in which a family is torn apart by false allegations of incest. For her part, Hjorth insists Will and Testament is not autobiographical.

Hjorth is a highly regarded novelist in Norway; she has written more than twenty novels, and her second English-translated novel, the putatively fictional family saga Will and Testament, won the Norwegian Critics Prize for Literature. Will and Testament was also highly controversial. The novel’s protagonist, Bergljot, shares many conspicuous similarities with Hjorth, and in the novel Bergljot claims that her father sexually abused her when she was a child. Hjorth’s younger sister Helga condemned the book as lies, and in 2017 she published her own novel, Free Will, in which a family is torn apart by false allegations of incest. For her part, Hjorth insists Will and Testament is not autobiographical.

Long Live the Post Horn! has avoided such controversy—the blurring of fiction and reality here deals in the postal, not the personal—and the novel has garnered much praise, with the New York Times declaring it “the best post office novel ever written.” It’s a story about mail delivery, for sure, but it’s also a story about personal growth and political awakening. As Ellinor observes, reading letters from the postal union representatives pleading their case, “It wasn’t the individual words, the individual word, the individual sentence… but the feeling that rose from the paper, it had a presence, an immediacy as if what was written wasn’t imagined but actually lived.” As Ellinor attempts to engage, to gather momentum, to preserve both the postal service and her own burgeoning sense of self, I can’t help but cheer for her newly emerging life—a life actually lived.

“Silencing writers is central to the traditional writing workshop model,” Chavez writes; it dates back to 1936, when Iowa became the first degree-granting program for writing. With primarily white faculty, students, and reading list, the workshop has long been a space for “safeguarding whiteness as the essence of literary integrity.”

“Silencing writers is central to the traditional writing workshop model,” Chavez writes; it dates back to 1936, when Iowa became the first degree-granting program for writing. With primarily white faculty, students, and reading list, the workshop has long been a space for “safeguarding whiteness as the essence of literary integrity.” Guillermo Rosales’s The Halfway House is a brilliant and stark portrait of what it’s like to live in multiple rings of exile, not unlike Dante’s multiple rings of hell. When the novel’s protagonist, William Figueras, arrives in Miami, his relatives expect to embrace a young Cuban exile ready to make it big in America. Instead, they lock eyes with someone they barely recognize—a rail thin stranger who hurls insults at them through missing teeth and is suffering from paranoia. Figueras is admitted to a psychiatric ward that day. He escapes Cuba only to enter the U.S. and be exiled again to the broken mental health care system, ending up in a privately-run halfway house that’s one tier better than living on the streets.

Guillermo Rosales’s The Halfway House is a brilliant and stark portrait of what it’s like to live in multiple rings of exile, not unlike Dante’s multiple rings of hell. When the novel’s protagonist, William Figueras, arrives in Miami, his relatives expect to embrace a young Cuban exile ready to make it big in America. Instead, they lock eyes with someone they barely recognize—a rail thin stranger who hurls insults at them through missing teeth and is suffering from paranoia. Figueras is admitted to a psychiatric ward that day. He escapes Cuba only to enter the U.S. and be exiled again to the broken mental health care system, ending up in a privately-run halfway house that’s one tier better than living on the streets.

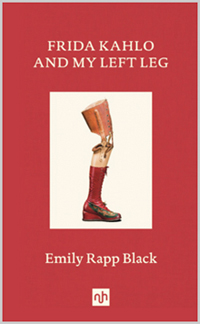

Frida Kahlo’s likeness appears on tote bags, t-shirts, mugs, refrigerator magnets, coffee table coasters and more; she has her own action figure. One of the most recognizable artists in the world, Kahlo symbolizes feminist strength, cultural pride, and the sharp essence of pain. In her poignant and deeply felt book Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, Emily Rapp Black interrogates the way in which Kahlo is reduced to a female artist whose muse is bodily and emotional suffering. Pain is not a muse, Rapp Black argues. “I do not believe that suffering was Frida’s main characteristic, because suffering does not create art, people do.” She adds that, yes, “[Frida] painted in bed. Create or die. That’s very different from ‘being inspired.’”

Frida Kahlo’s likeness appears on tote bags, t-shirts, mugs, refrigerator magnets, coffee table coasters and more; she has her own action figure. One of the most recognizable artists in the world, Kahlo symbolizes feminist strength, cultural pride, and the sharp essence of pain. In her poignant and deeply felt book Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, Emily Rapp Black interrogates the way in which Kahlo is reduced to a female artist whose muse is bodily and emotional suffering. Pain is not a muse, Rapp Black argues. “I do not believe that suffering was Frida’s main characteristic, because suffering does not create art, people do.” She adds that, yes, “[Frida] painted in bed. Create or die. That’s very different from ‘being inspired.’”