And now for the third installment in Malvern Books’ arbitrary and occasional Poetry Month A-Z series…

E is for Eady, Cornelius

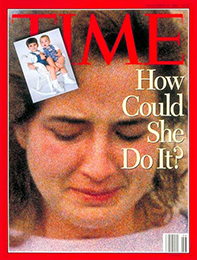

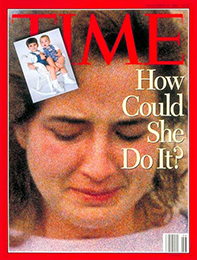

Remember Susan Smith, the shitty mom from Union, South Carolina? On October 25th, 1994, she told police she’d been carjacked by a stranger, who forced her out of her Mazda Protegé and drove away with her two young sons still in the back. She appeared on television, pale and twitchy, begging for their safe return: “I would like to say to whoever has my children, that they please, I mean please, bring them home.” But she failed repeated polygraphs—that little blue line always stuttered when they asked, “Do you know where your children are?”—and nine days after she reported the crime, she was arrested: Susan Smith had rolled the car into a lake with her kids inside, and left them to drown.

So Susan Smith was a Very Bad Mom, and the media loves a bad mom—the story was front page news for weeks. The case prompted a few peculiar strangers to make YouTube tribute videos in honor of her dead children, and the videos all come with a string of comments that pretty much blur into one: “She needs to rot in hell for what she did to those sweet innocent boys.” But keep scrolling down and you find: “A curse to these devils, always placing blame on other races for their own shit… they need to worry about their own race, devils devils devils.” Yes, Susan Smith had been very clear: her imaginary carjacker was an African American, a dark man dressed in a dark shirt and wearing a knit cap. “A black man did it”: the racial hoax. In 70% of cases where someone commits a crime and blames it on a fabricated transgressor of another race, the real criminal is white, and their invented assailant is black.

In his 2001 collection, Brutal Imagination, poet Cornelius Eady addresses the role of the black man in white America. In the collection’s second cycle, “Running Man,” Eady’s poems draw on the libretto for his 1999 music-drama of the same name (and for which he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize). But it’s the first, eponymous cycle of the collection that directly addresses the Susan Smith case and the concept of the racial hoax, with Eady adopting the persona of Smith’s imaginary black attacker.

In his 2001 collection, Brutal Imagination, poet Cornelius Eady addresses the role of the black man in white America. In the collection’s second cycle, “Running Man,” Eady’s poems draw on the libretto for his 1999 music-drama of the same name (and for which he was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize). But it’s the first, eponymous cycle of the collection that directly addresses the Susan Smith case and the concept of the racial hoax, with Eady adopting the persona of Smith’s imaginary black attacker.

How I Got Born

Though it’s common belief

That Susan Smith willed me alive

At the moment

Her babies sank into the lake

When called, I come.

My job is to get things done.

I am piecemeal.

I make my living by taking things.

So now a mother needs me clothed

In hand-me-downs

And a knit cap.

Whatever.

We arrive, bereaved

On a stranger’s step.

Baby, they weep.

Poor child.

This character, referred to as Mr. Zero, acts as a kind of guide, leading us through this all-too-familiar scenario, where “everything they say about me is true.” The narrator also recalls being summoned by Charles Stuart, the Boston man who shot and killed his wife, then told the police the murderer was a young, black male:

I sat with Charles the way I sit

With Susan; like anyone, and no one,

Changing clothes,

Putting on and taking off ski caps,

Curling and relaxing my hair,

Trying hard to become sense.

In the cycle’s final poem, “Birthing,” words from Susan Smith’s handwritten confession (in italics) are interwoven with the narrator’s voice:

When I left my home on Tuesday, October 25, I

was very emotionally distraught

I have yet

to breathe.

I am in the back of her mind,

Not even a notion.

A scrap of cloth, the way

A man lopes down the street.

Later, a black woman will say:

“We knew exactly who she was describing.”

* * *

I felt I couldn’t be a good mom anymore, but I didn’t want

my children to grow up without a mom.

I am not me, yet.

At the bridge,

One of Susan’s kids cries,

So she drives to the lake,

To the boat dock.

I am not yet opportunity.

* * *

I had never felt so lonely

and so sad.

Who shall be a witness?

Bullfrogs, water fowl.

The poems were written to be performed; this first cycle was adapted for an award-winning off-Broadway play. The language in Brutal Imagination is plain and straightforward, almost disarmingly serene. It’s a powerful collection, unabashedly political, but never preachy: the narrator, this conjured scapegoat, delivers his message in a voice so calm, so quiet, so resigned—it’s utterly chilling.

If you decide to wash your car,

If you decide to mail a letter,

I might tumbleweed onto a pant leg.

You can stare, and stare, but I can’t be found.

Susan has loosed me on the neighbors,

A cold representative.

The scariest face you could think of.

In an interview, Eady says of Brutal Imagination:

It’s an examination of what the stereotypes are made of, the elements that we’ve used to make those characters what they are, our belief system. One thing that fascinated me about the story was how easy it was for Susan Smith to tap into that. She just pulled it out of the ether. I know when it happened. Between the time she sees the car’s taillights go under the lake and when she’s walking from the lake across the highway toward the first house she finds. In that little space of time, she’s thinking, Who did this? Someone’s got to have done this. Someone’s got to be blamed for this. It’s a black guy, and he’s wearing a cap, and he pushed me out of the car. She’s thinking this as she’s walking toward the house. It’s just so easy because it’s plausible. That was the scariest part, how easy it was for her.

American poet Louise Glück isn’t the cheeriest duck in the pond—loneliness, divorce, and rejection are her favored themes—but she can shoulder the weight of myth like no one else, and her spare, intimate, unflinching voice is utterly compelling. If you’re new to Glück, her Pulitzer-Prize-winning collection, The Wild Iris (1993), is a great place to dive in, and the more recent Averno (2007) is also wonderful. Here’s a poem from Averno to get your weekend off to a hellishly good start:

American poet Louise Glück isn’t the cheeriest duck in the pond—loneliness, divorce, and rejection are her favored themes—but she can shoulder the weight of myth like no one else, and her spare, intimate, unflinching voice is utterly compelling. If you’re new to Glück, her Pulitzer-Prize-winning collection, The Wild Iris (1993), is a great place to dive in, and the more recent Averno (2007) is also wonderful. Here’s a poem from Averno to get your weekend off to a hellishly good start:

In his 2001 collection,

In his 2001 collection,  Were you forced to memorize lengthy bits of the

Were you forced to memorize lengthy bits of the  If a serenade is an evening love song, an aubade is its early bird equivalent. Aubades often recount tales of adulterous lovers who must part company as the sun comes up, and they were quite the thing in the freaky Middles Ages, when troubadours roamed the world, playing their annoying fiddles and reciting aubades to anyone who would listen. The aubade then passed out of fashion for a while—sixteenth-century poets preferred to bang on about unrequited love, which meant very little romping at dawn—but the form enjoyed a brief revival in the seventeenth century, with John Donne’s “

If a serenade is an evening love song, an aubade is its early bird equivalent. Aubades often recount tales of adulterous lovers who must part company as the sun comes up, and they were quite the thing in the freaky Middles Ages, when troubadours roamed the world, playing their annoying fiddles and reciting aubades to anyone who would listen. The aubade then passed out of fashion for a while—sixteenth-century poets preferred to bang on about unrequited love, which meant very little romping at dawn—but the form enjoyed a brief revival in the seventeenth century, with John Donne’s “ About suffering they were never wrong,

About suffering they were never wrong,