Julie recommends Joy of Missing Out by Ana Božičević:

Walking home from the first meeting of Line/Break (Malvern’s Poetry Book Club) I reveled in—and interrogated—a line from ol’ Walt Whitman, “Have you ever felt proud to get at the meaning of poems?”

Walking home from the first meeting of Line/Break (Malvern’s Poetry Book Club) I reveled in—and interrogated—a line from ol’ Walt Whitman, “Have you ever felt proud to get at the meaning of poems?”

Nope, not really. OK, well, maybe sometimes, but mostly, Great Godfather of American Poetry, poems leave me feeling stupid, wonderfully, happily stupid. What I end up understanding is only an outline, a shadow, a sense of all the ways in which a poem can inhabit feeling. It’s like holding hands with a ghost, and I love ghosts! If I do “get” a poem it’s usually a pretty bad one—far too easy to make sense of. I prefer mystification.

I can’t help it, I’m utterly wedded to the idea that poems encourage alternative ways of thinking, they invite and embolden us to ask, “What if the world was this way?” In Joy of Missing Out Ana Božičević could have, at some point, asked herself several what if questions. What if there were poems out there that spoke about late-night lonely lurkings on the Interweb? What if mental illness was spoken about openly? What if flat, innocuous words like “like,” “emoji,” “facebook” could be infused with new meaning? What if it were possible to pump fresh blood into a term like “LOL” which, at this point, might as well be a laughed-out corpse?

People, poets I mean, write about popular culture every day. Božičević has written poems with titles like “The Day Lady Gaga Died” (see Rise in the Fall). Others have dedicated entire works to a single pop figure (see Letters to Kelly Clarkson by Julia Block, or Mr. West by Sara Blake). Even what pops up on news feeds becomes fodder for poems. (See Daylight Savings Time Flies Like an Instagram of a Weasel Riding a Woodpecker & You Feel Everything Will Be Alright by Regie Cabico.) And now, anyone can be a pop figure. Social media has created hybrid famous people, “influencers,” and celebrity cats. We are a culture, in many ways, obsessed with technology, deriding it, revering it, needing it, shunning it. Google churns out more information than anyone could ever hope to absorb with just one measly brain.

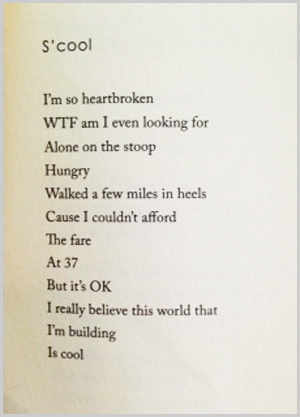

This is to say that, in the hands of a lesser poet, poems riddled with tech speak risk becoming imitations of imitations. The <3 imitates a smooch, deeper meaning can only go so far, unless you’re Božičević and you shape a book of poems around bigger ideas: love, loss, loneliness, and perhaps most importantly, estrangement, the feeling of being locked out of your own life. In the poem “S’cool,” she writes:

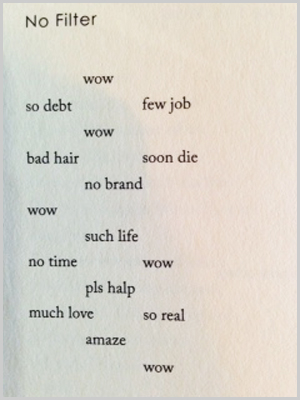

The last line echoes the elision in the title. The “s’cool” of hard knocks, the school of disappointment, the Newer New York School of Poets in an era when everyone is urged to build a “brand.” Božičević plays with this idea further in “No Filter,” a scattershot-spaced poem that reads:

This poem jostles between two states, amazement or “amaze” and a catalog of suck. I love this poem. It’s shorthand for a weakened attention span. Gone are the days of trying to reach Wordsworthian or Keatsian sublimes, a simple “wow” works instead. Or maybe the “wow” is a sarcastic teenager shrugging. Whatever the “wow” is, or represents, the poem manages to capture how I feel on a near daily basis.

Božičević came to the U.S. at age nineteen from Croatia. She’s fluent in English, and she can’t help but call herself an American poet. To become an American poet also means gaining cultural fluency, not just in books, music, and art, but things like Tumbler, #__, Starbucks, 7/11, and CVS.

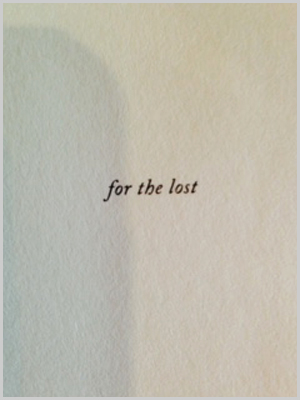

JOMO lays out all of the ways in which one can be an outsider. The speaker of the poems is positioned not only as being an outsider as an artist (poets are notorious outsiders) but as a woman, a queer woman, an immigrant, a non-native speaker (let’s remember this land’s first language was not English), and someone with a mental illness.

She outs herself in a variety of ways and these ways all lead back to the beautiful dedication at the beginning:

The lost don’t just need a voice to relate to, they need a little levity sometimes, and Božičević delivers on that front.

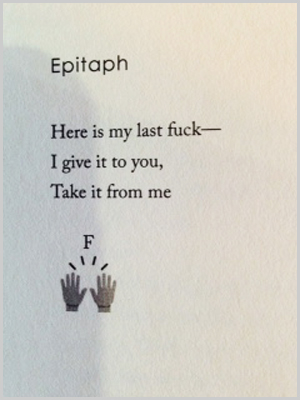

It’s devastating to wallow, even more so when it’s done with full awareness. Božičević uses humor as a way to shake off despair the way a wet dog does lake water. It’s both a distancing device and a means for getting closer. As a poet, she’s perhaps painfully aware of the almighty “reader,” the person who could easily stop reading, shut the book, and exit the poem forever. She embraces this prospect, teases it a little, and even dares the addressee to bounce.

I don’t think the only value of poetry is whether or not you relate to it on a personal level, that’s a very narrow experience of art in general, but, for me, being able to relate to a speaker is certainly a viable entry point because I read to connect as much as I read to learn. I found a genuine appreciation for lines such as “I’ll be so mad / If love turns out not to be a person,” or “Where’s my drugs,” or a “Moth is just a loser butterfly.”

Anne Waldman called Božičević “one of our most rambunctious and charismatic poets,” a real lifesaver, someone who can in fact make you feel better.

It’s fitting that JOMO begins with a blessing and ends with dancing; the last line of the book is “And I shake my ass,” which invites several readings, one literal, the action of ass-shaking, one that means, “And I continue to live,” and one, that, if taken in isolation, could mean “I jostle my donkey,” all of these interpretations are cause for celebration.