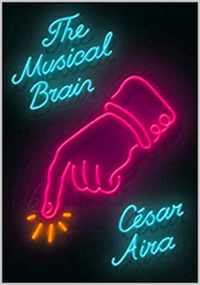

Claire recommends The Musical Brain by César Aira:

My first foray into the wild mechanics of Aira’s fiction, this collection of short stories feels like it has been spun out of the webby brainwaves of a mad scientist. Aira is known as the Latin American master of microfiction, having published ten short novels in nine years with New Directions. But there’s something wholly unexpected about the way these short stories read like experiments “approaching the edge of the chasm that separates an ending from a continuation.” (p. 331) His genius is beyond question, though its expression is so strange, that after reading any one of these stories, your brain may be full of nothing but questions, but also delight.

My first foray into the wild mechanics of Aira’s fiction, this collection of short stories feels like it has been spun out of the webby brainwaves of a mad scientist. Aira is known as the Latin American master of microfiction, having published ten short novels in nine years with New Directions. But there’s something wholly unexpected about the way these short stories read like experiments “approaching the edge of the chasm that separates an ending from a continuation.” (p. 331) His genius is beyond question, though its expression is so strange, that after reading any one of these stories, your brain may be full of nothing but questions, but also delight.

Are you looking for the kind of story that takes seriously the business of philosophy, human nature, high art, and the limits of the reasoning mind, with a plot that focuses on two men, one with hands the size of the rest of his body, and one with feet the size of the rest of his body? Look no further.

These are stories, yes, but they are also experiments in thought. Though the language is rich and heavily laden with the detailed imagery of surrealism, each story seems to operate by some mechanism other than plot, often implementing weird, unpredictable math, accumulating rapidly and beyond the limits of reason. It is clear that Aira is invested in “the art of thinking.” (p. 333) He writes himself into the corner of an irresolvable paradox over and over again, and the real pleasure in reading his work is to witness the otherworldly acrobatics of his seemingly unplanned escapes.

As you find yourself moving through the “only primates allowed” tea party thrown annually on God’s birthday, and suddenly reality is thrown out of whack by a single, interloping particle, swinging the party upside down in multiple dimensions at once, you may find yourself thinking, “There must be something in that tea.” (p. 211) There certainly is something in the tea of these stories, something delightful that makes you smarter even as it ushers you into a state of pure delirium.

As Aira investigates an imagined life of the titular avant-garde jazz pianist in the story “Cecil Taylor,” he describes Cecil’s free jazz style and it feels distinctly self-referential: “causation was operating at a higher level.” (p. 333) And as in avant-garde jazz, it feels at times in these stories as though Aira is intentionally “creating unbearable situations in thought.” (p. 331) If you push through the difficulty of reading these stories and enduring these momentarily unbearable thought experiments, you will be greeted somewhere over the hill by the rush of falling under his spell. In “A Thousand Drops” the paint of the Mona Lisa evaporates into droplets which each go on to live their own lives, exploring the world, getting into trouble, falling in love. And as if this concept wasn’t strange enough, the story takes a cosmic turn, delivering us into the conceptual quark-gluon plasmas of space, where we bear witness to a beautiful love story between Gravity and Perspective, the imagery of which has cast a lasting enchantment over me.

Here’s what I learned: To read César Aira is a challenging and sincere thrill, and to enter into these stories one must prepare herself to encounter the “inherent incongruence of the higher geometries.” (p. 336)