The Age of Skin by Dubravka Ugresic

by JP Poole

My copy of Dubravka Ugresic’s The Age of Skin is highlighted, underlined, and peppered throughout with asterisks, exclamation marks, and messy notes. Why? Because Ugresic might just be one of the best essayists on the planet; her praises are sung by the likes of Susan Sontag, Joseph Brodsky, and Charles Simic. The New Criterion stated, “As long as some, like Ugresic, who can write well, do, there will be hope for the future.” Indeed, the future is critical to her work. As long as there are those who threaten to erase history, deny genocide, the Holocaust, mass executions, the rape and murder of innocents, as long as war criminals roam free and lead carefree lives, and as long as nationalism rears its monstrous head all over the globe, then the future remains a distant dream unless we are able to reconcile our past. Documentation, writing itself, resists that ever-pressing historical erasure, and is charged with the moral purpose of setting humanity back on some sort of sane and rational course.

Ugresic takes on the heavy baggage of the world by seesawing between humor and horror. In the title essay The Age of Skin, she talks about the tricky process of embalming Lenin’s body, noting that Lenin’s Mausoleum also sells caskets, including a pricey special edition made out of crystal called the “Al Capone,” so named after the casket pictured in The Godfather. In a single paragraph she might mention the author of Fifty Shades of Grey, Maxim Gorky, and Shakespeare.

In meticulously documenting and cataloging modern life, her essays are like packed storage units, stuffed to the gills with the artifacts of arts and culture. Like a museum tour guide, she leads us through the bleak detritus, capitalist’s junk, and beautiful polished antiques of lost eras, forging a path through her material in a way that readers can comprehend. To the left, we see a flag from a war-torn nation, to the right, we see refugees bonding over baklava.

In meticulously documenting and cataloging modern life, her essays are like packed storage units, stuffed to the gills with the artifacts of arts and culture. Like a museum tour guide, she leads us through the bleak detritus, capitalist’s junk, and beautiful polished antiques of lost eras, forging a path through her material in a way that readers can comprehend. To the left, we see a flag from a war-torn nation, to the right, we see refugees bonding over baklava.

In a Nexus Institute lecture, she talks about deprofessionalization—when education, qualifications, and even basic levels of competence are no longer required for key political positions and important leadership roles. Just this week, I read Anne Applebaum’s incredible essay “The Collaborators,” published in The Atlantic. She states that loyalty is the main ingredient any corrupt regime seeks out in order to maintain power. Applebaum offers the example of when Trump appointed Sonny Perdue, a businessman with an array of conflicts, a devotion to lobbyists and special interest groups, and zero objectivity, to Secretary of Agriculture. Perdue then hired his own team of individuals who also lacked qualifications, including a long-haul truck driver, whose resume boasted experience in “hauling and shipping agricultural commodities.” A domino effect of incompetence ensures that an entire political cabinet resembles a scene out of Dumb and Dumber, but with real-life consequences and drastic risks to public health and welfare. Ugresic makes a similar point in her book: tyrants don’t like being disagreed with, advised, educated, or told what to do—they like yes-men; they like to be in charge of their own rose-tinted legacy.

Ugresic left the former Yugoslavia in 1991 when the war began. In American Fictionary she writes about living in the cellar of her apartment building in Zagreb, with a bag of essentials ready and waiting at the door: “[a]t the sound of the air-raid warning siren we would run down to our cellars, improvised shelters, carrying the bags with us. In their bags many women brought along knitting needles and wool.” She was invited to the safe harbor of Amsterdam and has lived there ever since. “What saved a life,” she writes, “is a daily routine: feeding paper into the typewriter, writing an article…” As I read through her books, which largely home in on the tumult created by the Yugoslav war, I can’t help but see similarities with the rise of fascism in the U.S. My comparisons are inept and elementary, but I’m keen enough to understand that Ugresic possesses key insights into American politics; she saw the signs long ago. In fact, anytime a government begins to clamp down on (or discredit) scientists, artist, thinkers, professors, and doctors, you know there’s a problem.

Her essay “Good Morning, Losers!” is a loving ode to her highly educated friends, who’ve found themselves wondering where they’ve gone wrong in life. Their university degrees can’t compete with what today’s culture wants, self-fixated life-style bloggers, who seem to have found the elixir for eternal happiness. No one, no matter how intelligent, is completely free from pining after the perfect life. She writes: “Under Communism, a person could always blame the system, Communism itself; under capitalism we are all to blame for our own shortcomings.” Thus, her friend becomes fixated on the life of Jenn J., a beautiful woman with a beautiful family, who spends her time making eco-friendly cloth gift bags, bouncing between her Upper West Side home and cottage getaway.

Another friend, an astrophysicist, is out of a job. He’s left scrolling the internet for anything to keep himself afloat. A few clicks swerve off course. “There before him on the computer screen loomed Kim Kardashian’s large, oiled butt. The butt wasn’t moving, it watched my friend like a meteorite, a glacier, a star… Kim Kardashian’s butt came jumping off every website, the world over, wherever he clicked.” In this telling passage, a highly educated man is mocked by popular culture. The butt has achieved unrivaled success, where the astrophysicist is asking himself “where have I gone wrong, oh, how did I end up here?”

In the same essay, Ugresic shares her friend’s anxieties. People don’t seem to want cogent sentences anymore. “In the forty years I’ve been writing, we’ve reached a point where hardly anyone buys serious books anymore…” Instead, the publishing marketplace is clotted with influencers, such as the young British beauty expert Zoella, whose YouTube channel has over ten-million subscribers. Seeing the potential for teen-girl cat nip, Penguin snapped Zoella right up, publishing her book Girl Online, which she penned very little of, stating, “Of course I was going to have help from Penguin’s editorial team in telling my story.” Her “story” is one of wealth, privilege, bouts of anxiety, and plenty of hair products. When culture no longer maintains artistic, intellectual, and moral standards the reward is plump booties and advice on how to do hair. Just today, I was reading an article on a trusted news site when Google placed an ad for the company of hot available redheads.

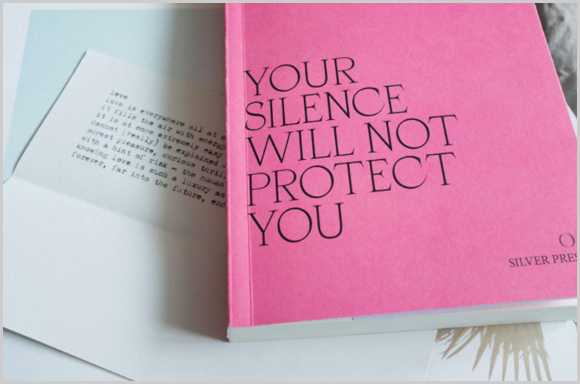

One of the elements I appreciated most about The Age of Skin is Ugresic’s claim that many of the political problems we see today hold deep roots in misogyny—a hatred of women is key in maintaining any dictator’s control. “Misogyny” she writes, “functions like radiation. It is invisible and not a single person is spared by it.” A very visible reminder of long-standing efforts to silence women shows up in her essay “The Scold’s Bridle.” If you google the term, you’ll discover a frightening torture device straight out of The Handmaid’s Tale, designed to suppress women with loose tongues. Eventually the iron cage with a metal bit to prevent speech is no longer needed because women mute themselves. They internalize the belief that their thoughts have no place in the spheres of religion, politics, or academia. Want proof? Ugresic asks us to picture a “public intellectual” in our minds. A male figure, perhaps wearing a tie and spectacles, is bound to materialize first and foremost. Indeed, I had trouble thinking of someone who might be considered an important female intellectual on par with the no-longer-living Susan Sontag. (Ugresic is one of the few that came to mind.) Then again, I had difficulty conjuring a contemporary public intellectual at all. Knowledge isn’t exactly revered these days. Ugresic understands this, which might be why she juxtaposes carbohydrate-heavy popular culture—La La Land, Nutella, and Bill Clinton/James Patterson—with the nourishing art of Bohumil Hrabal, Mary Beard, and the sculptures of Bakic; she isn’t asking us to choose sides, to make only “healthy choices,” but to notice, observe, and discover our own path out of the darkness and into the light.

In meticulously documenting and cataloging modern life, her essays are like packed storage units, stuffed to the gills with the artifacts of arts and culture. Like a museum tour guide, she leads us through the bleak detritus, capitalist’s junk, and beautiful polished antiques of lost eras, forging a path through her material in a way that readers can comprehend. To the left, we see a flag from a war-torn nation, to the right, we see refugees bonding over baklava.

In meticulously documenting and cataloging modern life, her essays are like packed storage units, stuffed to the gills with the artifacts of arts and culture. Like a museum tour guide, she leads us through the bleak detritus, capitalist’s junk, and beautiful polished antiques of lost eras, forging a path through her material in a way that readers can comprehend. To the left, we see a flag from a war-torn nation, to the right, we see refugees bonding over baklava.

Taisia Kitaiskaia has been channeling the voice of a witch for seven years. Beginning with an advice column in the Hairpin (a defunct website co-edited by Jia Tolentino), then morphing into a collection titled

Taisia Kitaiskaia has been channeling the voice of a witch for seven years. Beginning with an advice column in the Hairpin (a defunct website co-edited by Jia Tolentino), then morphing into a collection titled