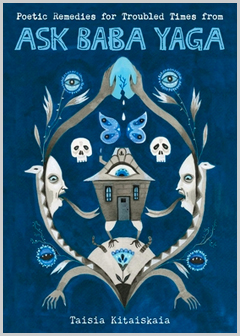

JP Poole recommends Poetic Remedies for Troubled Times from Ask Baba Yaga by Taisia Kitaiskaia

Taisia Kitaiskaia has been channeling the voice of a witch for seven years. Beginning with an advice column in the Hairpin (a defunct website co-edited by Jia Tolentino), then morphing into a collection titled Ask Baba Yaga: Otherworldly Advice for Everyday Troubles, Kitaiskaia’s Baba now returns at a critical time, when many of us are aching for comfort, amidst isolation and a world on fire.

Taisia Kitaiskaia has been channeling the voice of a witch for seven years. Beginning with an advice column in the Hairpin (a defunct website co-edited by Jia Tolentino), then morphing into a collection titled Ask Baba Yaga: Otherworldly Advice for Everyday Troubles, Kitaiskaia’s Baba now returns at a critical time, when many of us are aching for comfort, amidst isolation and a world on fire.

Who exactly is Baba Yaga? She’s a figure from Slavic folklore, an ageless witch, both hideous and hunched, who lives in a magical house set atop chicken legs. Unlike witches eager to turn children into stew, Baba Yaga’s interests lie elsewhere, deep in the forest where she lives. An off-the-grid naturalist of sorts, she offers advice when she feels like it and only to humans she senses are truly in need.

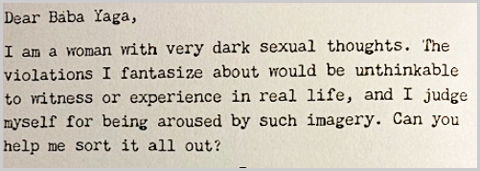

This is one of the many elements that sets Kitaiskaia’s advice apart. Unlike with a Dear Abby or a Dear Sugar variety wisdom-giver, those seeking advice can’t be certain what Baba will say, which, in a sense, makes their letters of appeal more vulnerable and real. Here’s an excerpt:

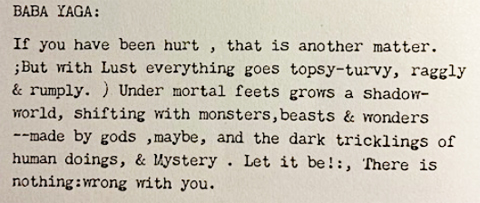

It would be all too easy to pull out a response that evokes an armchair psychologist. Baba does no such thing.

Using a poet’s sensibility, Kitaiskaia crafts a medicinal balm to set the advice-seeker’s mind and heart at ease. Nonce words such as “raggly,” “rumply,” and “tricklings” serve as a means of describing what’s difficult to say: that we all have dark thoughts sometimes but to be self-punishing only isolates us more. Baba might make singular words plural (feets) but she doesn’t make mistakes or mince words when something is important. She states upfront that if these dark thoughts stem from abuse “that is another matter.”

It’s easy to see how a book of this variety might fall into a trap of being cartoonish and overly-cute. Katy Horan’s dark and beautiful illustrations instantly bulldoze this potential pitfall. Horan’s bold images form a perfect companionship with the strong and independent voice of Baba—and together they fashion a protective talisman against the things that hurt.

Never childish, readers can trust that, even while embodying the voice of a crone, Kitaiskaia listens closely, she doesn’t forget the importance of what she’s doing, and, as a skilled poet, each word, each punctuation mark, each typographic spacing is fat with meaning. What echoes back is wonderfully dissonant—alive with Beasts and Trees (capitalized)—and her responses are always carefully curated to each individual’s needs, offering, in a sense, the gift of a personalized poem.

Poetic Remedies for Troubled Times is filled to the brim with people looking for answers: is it possible to find a “good guy” in the era of #MeToo, how do you handle a handsy father-in-law, how do you get your family to accept your gender identity, how do you tell your children things will be okay when you also share their fears.

Readers will connect to this cacophony of voices, speaking out of the void, and find solace in Baba’s idiosyncratic word-spells. When she says, “I have watched the Earth turn over many times… the Changing brings fear & sorrow, but wonder lurks in the same field,” it’s easy to believe. She’s attuned to something ancient, primal, and uniquely wise. What poetic remedies offer that practical advice cannot is a path to self-discovery through the forest of the imagination. In sum, perhaps it takes a witch to remind us that, as long as the world contains plants, animals, and human-ly creatures, we are never truly alone.